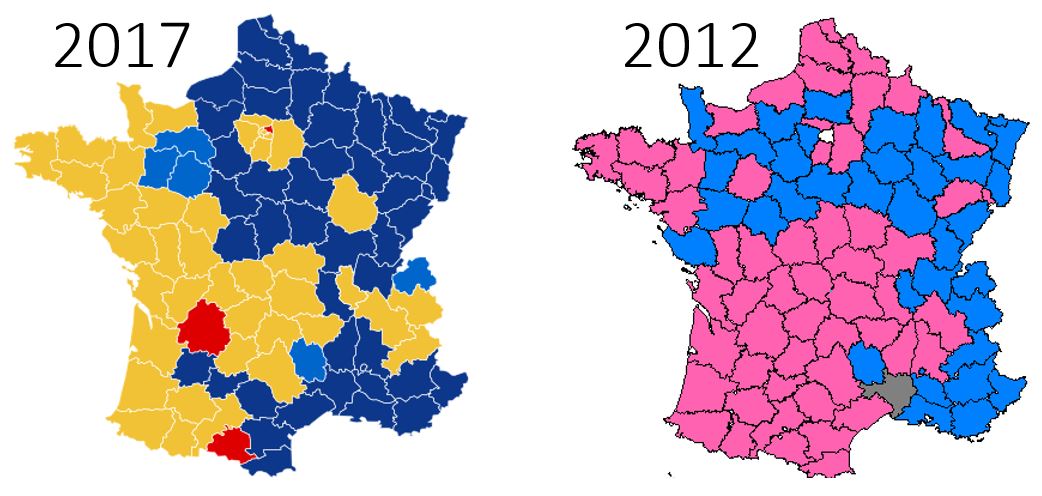

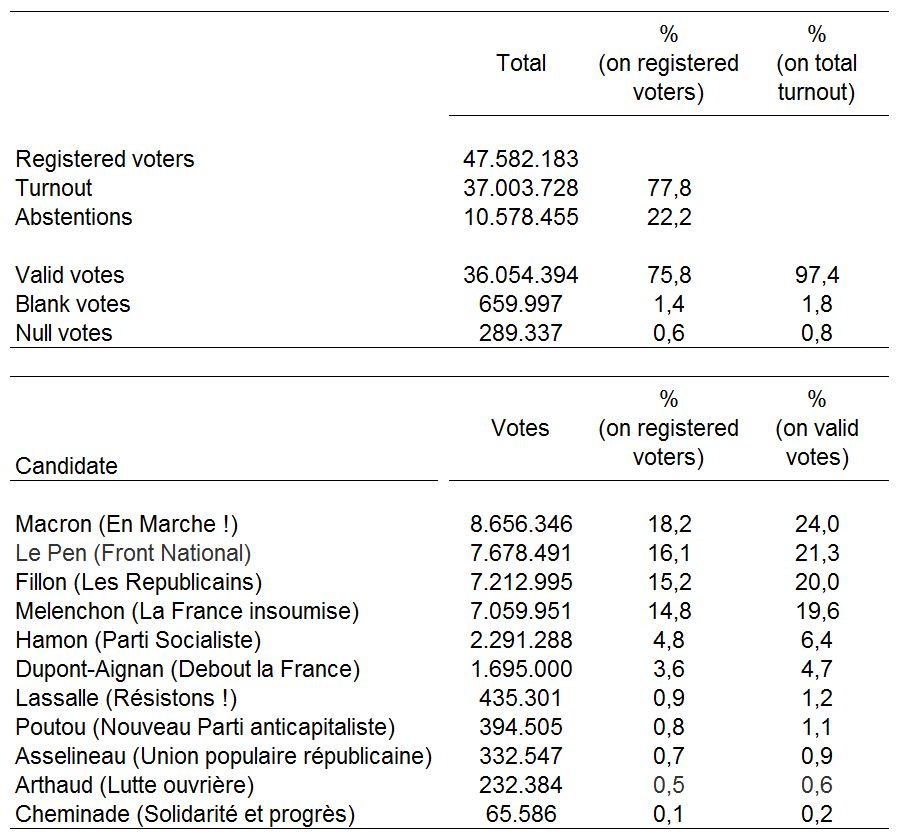

The eventful and unconventional campaign for the French presidential elections (partly) came to an end on Sunday night. Centrist candidate Emmanuel Macron (24,0%) and radical right Marine Le Pen (21,3%) of the Front National have both qualified for the run-off of the presidential election. Even though polls had predicted this results in the months coming to the election, it still constitutes a surprise. The outcome is historically close, and 4 candidates have gathered around 20% of the electorate, and both mainstream parties have been eliminated. After Macron and Le Pen, right-wing candidate François Fillon (20,0%) and radical left Jean-Luc Mélenchon (19,6%) came short of making it to the second round. On the left, 2017 marks the historical result of Mélenchon, at the same time as one of the lowest scores of Benoit Hamon, representing the Socialist Party of outgoing president Francois Hollande. The fact that the latter had renounced to compete for reelection (because of his very low approval ratings) had completely opened the presidential race, although the campaign had been mostly centered on political and financial scandals.

Tab. 1 – Results in the first round of 2017 French presidential elections

Macron’s result is particularly impressive as the candidate was virtually unknown a few years ago, and he led the candidate without the support of any established political party. He managed to gather individuals from the left and the right to create his own centrist movement: En Marche. The same strategy worked with voters. Macron’s campaign was articulated around two types of issues. First, he embodied the idea of political renewal – and mostly renewal of the political personnel. This issue has been the core of the campaign, and although all his opponents have targeted Macron as the “candidate of the system” and the heir of Francois Hollande, he seems to have captured this aspiration in public opinion because he was relatively unknown before the campaign, and because he sides with no traditional political party. Additionally, Macron mostly campaigned on valence issues (that is, issues that are mainly consensual) such as supporting economic growth, and making the improvement of education as his top campaign priority. He was also the only openly pro-European candidate, in a campaign influenced by eurosckeptics candidates (Le Pen, Mélenchon).

Marine Le Pen’s result is both a success and a disappointment. The candidate of the Front National will compete in the second round of the election only for the second time of this party’s history (after her father, Jean-Marie Le Pen in 2002). She articulated her campaign on issues where her positions clash the most with other candidates: immigration and euro-scepticism. Particularly, Marine Le Pen was the only major candidate to support the abandon of the euro, and to support a referendum on the participation of France to the EU. Yet, Le Pen had been polling over 25% and in first positions for several months before the campaign. Finishing second with less than 22% of the vote will prove a challenge to gather a majority for the second round; especially this (up to now) no other candidate or party has called to support her. They have rather called for the “Republican Front” and to support Macron in order to avoid the FN taking power.

Francois Fillon is the major loser of this election. As he won the primaries of the center and the right in 2016, he appeared as the strongest contender for the presidency. After the extremely unpopular term of Hollande, Les Républicains, the mainstream conservative party considered this election to be “impossible to lose”. Yet, Fillon’s campaign has been completely focused on the political and financial scandals he was involved in. Fillon decided to carry on his campaign, and portray himself as the victim of a political conspiracy rather than stepping down (as many of his fellow party members were advising). Coming third is likely to have important consequences on the mainstream right party, as followers and voters will be divided between a centrist Macron-leaning option, and a more radical and conservative trend. Acknowledging his defeat, Fillon has called his supporter to vote for Macron in the second round.

The cumulated score of the Left (Mélenchon and Hamon) is over 25% of the vote, but in a completely unusual order. While Mélenchon managed to receive about 20% of the vote on a radical left platform which called for a transformation of the French political institutions through a constituent assembly drafting a new constitution and the renegotiation of all European treaties (supporting a French withdrawal in case of failure), Benoit Hamon only managed to get 6,4% of the vote, which is the lowest score of the Socialist Party since 1969.

No other candidate has reached 5%, which is also the threshold for obtaining public reimbursement of campaign expenses.

Overall, the campaign for the presidential election has been mainly centered on the reject of traditional parties and the renewal of the political personnel. Indeed, the two mainstream parties are both out of the second round for the first time in modern French history. The two contenders of the first round are outsiders of the usual party landscape: Macron has launched his own movement, while Le Pen leads the “anti-system” party (Sartori, 1976). Voters will be called to vote in the second round on May 7th, in an election that Macron seems very likely to win (to simulate the different scenarios, click here). The winner will then have to win a majority in the legislative elections of June (similar two-round system in single-member districts). In that case, outsiderness and have no support from traditional parties might prove to be less of an advantage than in the presidential election.

References

Sartori, Giovanni. (1976). Parties and Party Systems: A Framework for Analysis. New York: Cambridge University Press.