Dr. Alistair Clark,

Newcastle University

T: @ClarkAlistairJ

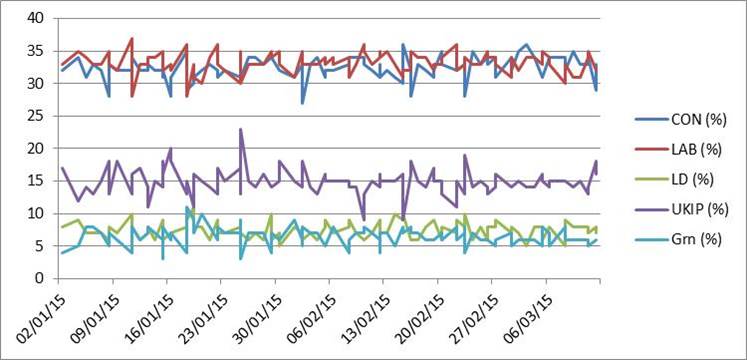

In my earlier blog for CISE on the UK’s 2015 general election, I noted how uncertain the polls were, with none of the two main British parties – Conservative or Labour – able to make a decisive break prior to polling day. I ended by suggesting that there was likely to be an investigation into the polling industry after election day. One of those predictions came true. Unfortunately for the reputation of political science predictions, it was that there will be an inquiry into the performance of the polling industry.

Expectations were of a hung parliament and weeks of post-election coalition negotiations. Instead, the results surprised everyone. The Conservative Party were returned to office with a small majority of 11 seats. There was no need for coalition or post-election deals. Labour had its worst performance since 1987. In Scotland, the Scottish National Party (SNP) achieved 50% of the vote and 56 (out of 59) Scottish seats.

Table 1: UK General Election 2015 Results

|

Vote share % |

+/- % |

Seats |

+/- |

|

| Conservative |

36.8 |

+ 0.8 |

330 |

+24 |

| Labour |

30.4 |

+ 1.5 |

232 |

-26 |

| Liberal Democrat |

7.9 |

– 15.2 |

8 |

-49 |

| SNP |

4.7 (50.0) |

+3.1 (+30.0) |

56 |

+50 |

| UKIP |

12.6 |

+9.5 |

1 |

-1 |

| Others |

7.5 |

+0.3 |

23 |

– |

Note: SNP share in brackets refers to the party’s vote share in Scotland only. Source: House of Commons Library Briefing Paper CBP7186.

Table 1 shows the final results. There were two big losers on the night. The first was the Labour Party under the leadership of Ed Miliband. I noted in my earlier blog that Miliband was regarded as a poor leader by the public. While he seemed to grow in stature during the campaign, this was far too little, and far too late. While Labour increased its share of the vote by 1.5%, it lost 26 seats across Britain. Many of these losses came in Scotland, where the party was reduced to only 1 MP by the SNP surge. However, the South of England has the highest concentration of seats in Britain. Labour made no gains there, except in London where it won an additional 7 seats and increased its share of the London vote by 7.1%. This was Labour’s largest gain anywhere in the country. Having led the party to its worst result since 1987, Miliband stood down as party leader the morning after the election. Labour now embarks upon a period of introverted debate about its direction before deciding on a new leader in September 2015.

The second big losers were the Liberal Democrats. Having participated in coalition with the Conservatives between 2010-15, the party was always expected to have a bad night at the polls. However, local incumbency was expected to help them win more seats than the polls were predicting. This did not happen. While party leader Nick Clegg kept his seat, only 7 other Liberal Democrats were elected across Britain. The party lost 49 seats, failed even to achieve 8% of the vote, and saw itself go from being the third largest party in the House of Commons, to being overtaken by the SNP. The Liberal Democrats were caught in the classic squeeze that affects many smaller coalition partners. They were blamed by Labour voters for having supported the Conservatives, blamed by Conservative voters for having stopped the Conservative Party’s more radical measures, and they were also hindered by having to relinquish so many of their own high-profile promises, most notably on student tuition fees. Clegg resigned the morning after the election and the Liberal Democrats now also embark on the search for a new leader from their much reduced group of parliamentarians.

The stars of the election were the Scottish National Party. Many commentators suggested that their rise in support is rooted in the 45% of Scots who voted for independence in the Scottish independence referendum in September 2014. While certainly important, singling that out as the sole cause is to misunderstand the party’s development over a longer period. It is often forgotten that the SNP won a majority of seats in the Scottish Parliament election of 2011 in a semi-proportional electoral system (a variant of MMP) designed explicitly to try to prevent any party winning a majority. It had governed Scotland as a minority administration from 2007-2011, and as a majority government from 2011. The core of the SNP’s strategy has been to present the image of a competent government, reasoning that without showing competence, they would be unlikely to win independence for Scotland. Party leader Nicola Sturgeon had a popular touch during the campaign. Indeed, many in England were asking if they could vote for her (they couldn’t as the SNP only stands in Scotland) and after the UK-wide leadership debates, she was one of the most searched for terms on Google in Britain. The SNP’s main competitors in Scotland, Labour, have been in long-term decline, but despite being on the winning side of the Independence referendum in 2014, have had no answer to the SNP who have seen a remarkable groundswell of support since then. The SNP went on to win 50% of the Scottish vote, a remarkable achievement against a background of general antipathy towards politics and politicians.

The other big winners were the Conservatives. Most Conservatives did not expect to win a majority in 2015, and expected some sort of post-election deal would be necessary if they were to retain power. Instead, from the moment the exit poll was released, a single-party Conservative government was always likely. That this was a majority was a surprise to virtually all commentators. The results bolster Cameron’s position considerably. He was heavily, but unreasonably, criticised for not winning a majority in 2010. The decision to hire Australian election strategist Lynton Crosby worked well for the party. The core message was economic competence, and that any Labour government with support from the SNP would put that at risk. This message was driven home time after time. At times the Conservatives anti-SNP rhetoric appeared to be putting the very Union at risk as it was very much perceived as anti-Scottish in Scotland. Yet it had the desired effect in England, driving voters into supporting the Conservatives. Cameron no longer has a coalition partner to deal with. This means that the Conservative manifesto will no longer be watered down by Liberal Democrats, and also that Cameron now has more positions in government to offer Conservative MPs to try to ensure their loyalty.

Finally, the right-wing populists of UKIP failed to meet the expectations generated by their winning performance in the 2014 European Parliament elections. Despite winning almost 4 million votes, and becoming the third largest party by votes, they won only 1 seat, which they already held after securing it in a by-election late in 2014. Party leader Nigel Farage yet again failed to win the seat he chose to contest, while they also fell short in other party target seats. However, the UKIP performance was noteworthy for two things. Firstly, the party won 118 second places. Some analysts suggest that this places the party in a good position for future gains. Secondly, the party made some major gains in votes against Labour, particularly in the north of England. In the North East of England, UKIP achieved a vote share of 16.7% and one constituency recorded a swing of around 19% away from Labour to UKIP. After almost every election, the party experiences a period of organisational in-fighting. 2015 has been no different. After initially resigning as party leader, Nigel Farage’s resignation was, bizarrely, rejected by the Party Executive. This led to an intra-party split over Farage’s leadership. Farage remains leader for the moment.

Analysis

A full analysis of the results will be undertaken in the months to come. Some points however are already clear. The first explanation is that economic competence won the day for the Conservative Party. By allowing themselves to be portrayed as the party of fiscal responsibility, the Conservatives were able to make this their key electoral issue, while also placing Labour in a position where it was always having to defend itself against claims of economic incompetence when in office at the beginning of the crash. Most Conservative themes were variations on this topic. For example, Labour’s potential reliance on the SNP in a hung parliament was cast by the Conservatives as being a recipe for chaos and undermining progress in clearing the deficit. Competence more generally also helped win the day for the SNP; being a competent government has been at the root of their appeal in Scotland since 2007.

Secondly, Labour were always on the defensive against a combined Conservative and, in Scotland, SNP challenge. It hoped that the UK had turned left in the aftermath of the financial crisis and that a ‘core vote’ strategy would be enough. Yet, Labour’s voters deserted the party in droves in Scotland, speeding up the decline the party had been going through there for some time. In England, Labour’s heartlands still largely voted for the party, but in much reduced numbers, particularly in the North of England. These are the ‘left behind’ working class voters who an elite-led Labour Party have been struggling to communicate with for more than a decade. Miliband was always unlikely to be able to reconnect with what once were traditional Labour voters. In the South of England, the problem was slightly different. Again, the traditional working class are part of the picture. However, the aspirational working class and middle class voter that Tony Blair was so good at appealing to also deserted the party and returned to the Conservatives. The ‘Big Tent’ Downsian strategy pursued by Blair and his colleagues will feature in debates of how to reposition the party.

Liberal Democrat voters have often been perceived to be centre-left. In 2015, the majority of Liberal Democrat voters in 2015 turned not to Labour, as some within Labour were hoping, but to their party’s coalition partners between 2010-15. The Conservatives appear to have done better among Liberal Democrat switchers, while in Scotland the sizeable Liberal Democrat vote turned to the SNP.

Turnout rose slightly to 66.2%, up from 65.1% in 2010. This small rise was largely because the election was much more competitive than some recent general elections have been. Scottish turnout was higher than the rest of the UK however at 71%. Such higher levels of participation are a legacy of the politicising nature of the Scottish Independence Referendum in 2014 which had registration levels of 97% and a turnout of 85%. Across the UK only 112 of the 650 constituencies actually changed hands between parties.

Consequences

A range of consequences flow from Cameron’s victory. The first and most important is that the UK will hold a referendum on the UK’s continued membership of the European Union. This will happen in either 2016 or 2017. While it has been promised before the end of 2017, Cameron’s majority has led to pressure to hold the ‘Brexit’ referendum in 2016. What is put to voters will depend on what Cameron is able to claim he has ‘renegotiated’ from the EU. Already the consequences of this referendum are being felt with EU citizens resident in the UK to be denied the vote in this particular decision. Most polls have staying in the EU as the preferred option, ahead of those who wish to leave. However, many newspapers are Eurosceptic if not explicitly for leaving. The ‘out’ campaign will be a very noisy one based on much misinformation, and led by some notoriously Eurosceptic Conservatives and UKIP. While Cameron has said he wishes to remain in, as have Labour, the Liberal Democrats and SNP, this is a referendum which could be lost.

Cameron’s position is now much stronger than it has ever been. However, his majority is small and his parliamentary party is very rebellious. Arguably he is now more at the mercy of his backbenchers than he was when in coalition when he could blame compromises on the Liberal Democrats. While the EU referendum will keep them in line for a while, there are numerous other issues they could rebel over, including the UK leaving the European Convention on Human Rights and replacing it with a ‘British Bill of Rights’.

Labour’s position is the most problematic. It is now 98 seats behind the Conservatives. The scale of its defeat suggests that it is likely to take two parliaments to even begin to think about getting back into office. While losing Scotland has become a high profile symbol of Labour’s problems, in truth Labour could have won every Scottish seat and still have fallen well short at Westminster. England is therefore crucial to the party’s renewal, and a vigorous internal debate is underway about how to appeal to the three diverse groups of voters that deserted the party: in Scotland; in Northern England; and in the Conservative voting south. Left-right and Blairite-Brownite distinctions are not necessarily helpful here. This is a very complex picture, and more so than simple dichotomies might suggest. While the leadership contest was inevitable, the risk for the party is that its internal debate again leaves political space free for the Conservatives to define the terms of competition in this parliament.

Finally, to the opinion polls which misled most commentators. More polling was done in the general election than at any previously, including extensive constituency polling. Yet, the results were wrong. Granted, opinion polls are snapshots, not predictions. However, it is inevitable that they will be used to form the basis of predictions. By being so consistently wrong, they are to undergo an inquiry. This was announced by the British Polling Council immediately after the election. It comes after criticism not just in the general election, but also in the Scottish Independence Referendum (see my previous CISE Blog). Differences between telephone polling and internet samples were found during the campaign. In reality, whatever interviewing method was used, the results remained well adrift from the eventual outcome. Numerous potential culprits have been identified – ‘shy Conservatives’ and ‘Lazy Labourites’ for example. The difficulty for pollsters is that if those they survey do not tell them who they will vote for, and then go and vote for them, there is little that polling companies can do. Expect considerable criticism and a report that will be pored over by political scientists, analysts and those interested in the political process. Whether some calls to ban the reporting of polls in the last few days of an election, as in France for example, will be implemented remains to be seen.

Biography

Dr Alistair Clark is currently Senior Lecturer in Politics at Newcastle University, a member of the UK Political Studies Association Executive and co-editor of British Journal of Politics and International Relations. His publications include Political Parties in the UK (Palgrave 2012) and recently in Public Administration an assessment of electoral integrity in Britain. He was Visiting Professor in Political Science & School of Government at LUISS Guido Carli in Rome in February-March 2015. E: alistair.clark@ncl.ac.uk. Twitter: @ClarkAlistairJ