Traduzione di Camilla Lavino.

Introduzione

Le elezioni per il Parlamento Europeo in Finlandia si sono svolte all’indomani delle elezioni parlamentari nazionali che hanno avuto luogo il 14 aprile 2019. In queste elezioni, il Partito Socialdemocratico (SDP) con il 17,7% dei voti ha di poco superato il partito populista di destra dei Veri Finlandesi (PS) che con il 17,5% è arrivato secondo e il conservatore Partito della Coalizione Nazionale (KOK), che con il 17,0% è arrivato terzo (De Lucia 2019).

Di conseguenza, la campagna elettorale per le elezioni del Parlamento Europeo è stata piuttosto breve. Il dibattito si è incentrato sul possibile successo dell’euroscettico PS, dal momento che si prevedeva che il partito avrebbe cavalcato l’ondata di euroscetticismo nelle elezioni europee (De Vries, 2018).

Si prevedeva poi che la prossimità delle elezioni avrebbe ridotto l’affluenza al voto delle europee, che nel 2014 era stata del 41,0% (Mattila 2003). La Finlandia ha avuto una delle più basse affluenze (10%) tra i giovani elettori (18-24) nel 2014, seconda solo alla Slovacchia (6%), nonostante vi fossero segnali che questa sarebbe potuta aumentare stavolta.

A causa del numero limitato di parlamentari da eleggere, è improbabile che anche spostamenti rilevanti nei risultati elettorali possano portare a vincere o perdere più di un seggio. Tuttavia, capire quali candidati vincano un seggio è sempre incerto nel sistema proporzionale a lista aperta che caratterizza la Finlandia, in cui gli elettori, piuttosto che le élite di partito, decidono quali candidati ottengono il seggio (von Schoultz 2018). Non era quindi chiaro, per la maggior parte dei partiti, quali candidati avrebbero conquistato dei seggi.

Partiti e temi

Dopo aver vinto le elezioni nazionali, l’SDP ha usato lo slogan “noi non facciamo Brexit, noi Fixit” – mostrato nella Figura 1 – per posizionarsi come il candidato più adatto per la gestione della presidenza finlandese dell’UE a partire da luglio 2019.

Fig. 1 – Principale slogan elettorale del SDP

Tuttavia, la maggior parte dei sondaggi suggeriva che sarebbe arrivato terzo o addirittura quarto nelle elezioni europee, ottenendo solo due seggi nel nuovo Parlamento Europeo. I candidati includevano l’ex-leader del partito Eero Heinäluoma, ma per il resto vi erano pochi candidati di spicco.

Insieme al SDP, il KOK e il partito di centro (KESK) sono tradizionalmente i tre attori principali del sistema partitico finlandese. Entrambi avrebbero dovuto perdere voti, tuttavia non era certo che ciò si sarebbe tradotto anche in una perdita di seggi. Si prevedeva che il KOK avrebbe perso voti, rimanendo tuttavia il partito più grande. Tre deputati uscenti al Parlamento europeo erano in corsa per la rielezione, ma l’ex primo ministro Alexander Stubb, che era stato un candidato popolare nelle elezioni del 2014, non partecipava questa volta. Il KESK rurale-liberista rischiava poi di perdere uno dei tre seggi nel caso in cui la battuta d’arresto subita nelle elezioni politiche si fosse verificata nuovamente. Due degli attuali deputati al Parlamento Europeo si erano ricandidati, ma erano sfidati da importanti quadri di partito.

Due partiti hanno sfidato il loro dominio. Il partito populista di destra dei Veri Finlandesi (PS) correva per consolidare la sua crescita e diventare il secondo partito in termini di voti, ottenendo così un terzo seggio nel Parlamento Europeo. La lista del PS includeva diversi candidati importanti, tra cui sei parlamentari neoeletti. Si prevedeva inoltre che la Lega Verde (VIHR) avrebbe guadagnato dei voti e alcuni sondaggi suggerivano che sarebbe potuto diventare il secondo partito in termini di voti e che avrebbe potuto vincere tre seggi grazie a ciò. Tra i candidati figuravano il veterano Heidi Hautala e l’ex leader del partito Ville Niinistö.

L’Alleanza di Sinistra (VAS) avrebbe dovuto mantenere un solo seggio, mentre il Partito Popolare Svedese (RKP) ha faticato per ottenere un unico seggio nel Parlamento Europeo. L’eurodeputata Merja Kyllönen era in corsa per la rielezione, ma aveva dichiarato pubblicamente che, se fosse stata eletta, non avrebbe assunto la carica in quanto preferiva sedere nel parlamento nazionale, all’interno del quale aveva ottenuto un seggio. L’RKP è invece un partito di minoranza che rappresenta principalmente la minoranza di finlandesi di lingua svedese. I sondaggi suggerivano come fosse improbabile che questi vincesse un seggio e, nonostante il partito fosse costantemente sottovalutato nei sondaggi, RKP ha dovuto mobilitare la maggior parte degli elettori di lingua svedese per difendere con successo il suo seggio in Parlamento. L’europarlamentare uscente Nils Torvalds ha guidato la lista che includeva diversi giovani candidati.

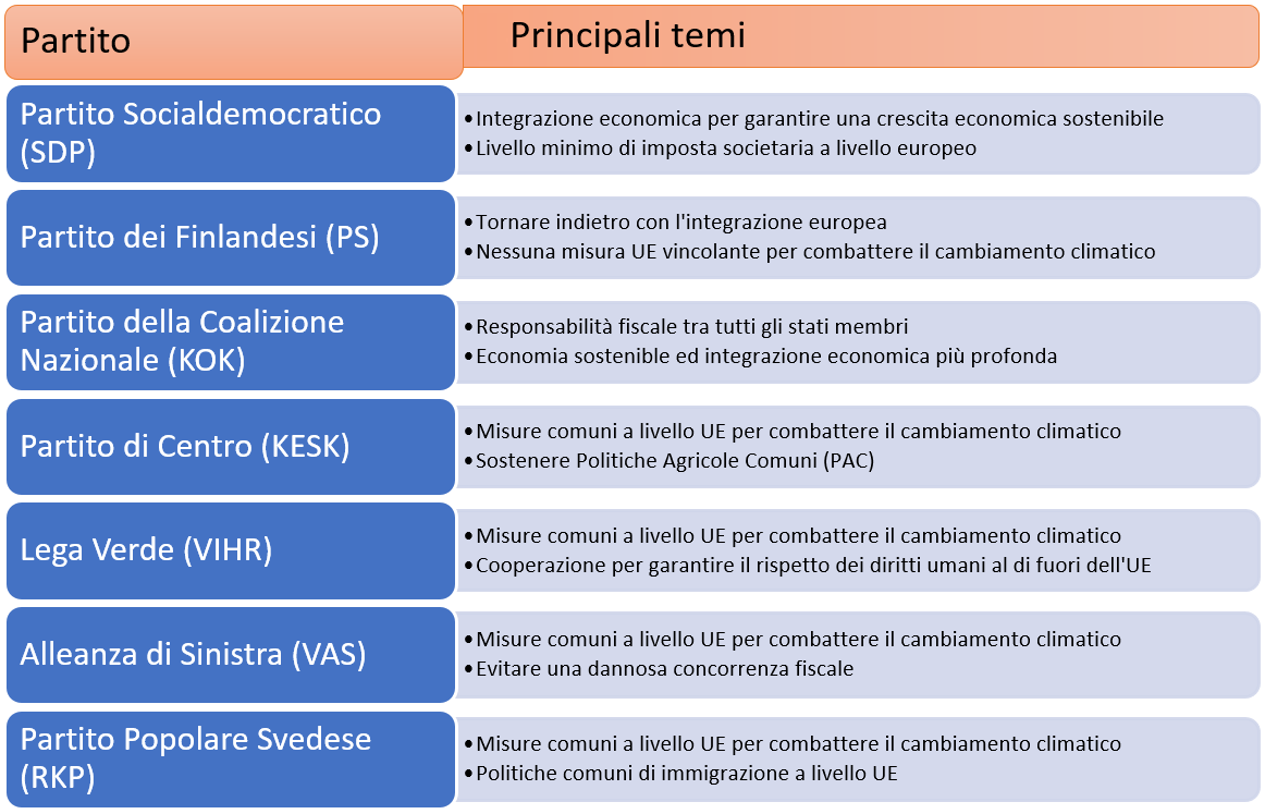

Sebbene l’integrazione sia stata sicuramente un tema discusso nei dibattiti, gran parte di questi si sono incentrati su argomenti genuinamente europei piuttosto che su questioni nazionali, come spesso accade in altri casi (Schmitt e Toygür, 2016). Tre temi di ambito UE sono stati particolarmente rilevanti: crescita economica, cambiamenti climatici e politiche migratorie. La Figura 2 mostra la posizione dei diversi partiti.

Il dibattito economico si è incentrato sull’evasione fiscale e sulla concorrenza. SDP, VAS e VIHR hanno sostenuto che la competizione sull’imposizione fiscale per le società costituisse una minaccia per il welfare state e che una tassa comunitaria minima avrebbe risolto il problema. Gli altri partiti hanno invece affermato che l’UE non dovrebbe prendere decisioni in materia di politica fiscale.

Il ruolo dell’UE nella lotta ai cambiamenti climatici è stato anche un tema scottante durante la campagna elettorale e qui il principale scollamento è stato riscontrato tra il PS e gli altri partiti. Il PS ha adottato la stessa strategia delle elezioni nazionali, mettendo in discussione la necessità di azioni immediate, e in particolare la necessità per la Finlandia di essere all’avanguardia nell’introduzione di tali misure. Sebbene vi siano delle differenze nel grado in cui tale problematica è stata sottolineata, tutti gli altri partiti erano in principio a favore all’idea di adottare delle misure a livello UE per combattere il cambiamento climatico.

Il dibattito sull’immigrazione è ruotato principalmente attorno ad un sistema di quote obbligatorie per gli stati membri. Qui la maggior parte dei partiti (SFP, KOK, VIHR, VAS, RKP) si sono mostrati favorevoli, mentre KESK sosteneva che l’idea fosse irrilevante dal momento che non sarebbe mai stata accettabile per gli altri stati membri, con infine il PS che invece si opponeva completamente all’idea.

Fig. 2 – Le posizioni dei diversi partiti sui temi al centro del dibattito

Il dibattito tra i principali candidati alla presidenza della Commissione Europea, svoltosi a Bruxelles il 15 maggio, ha suscitato l’interesse dei media nazionali. Diversi organi di stampa importanti hanno commentato il dibattito, il quale è stato generalmente percepito come un evento tranquillo in cui grandi disaccordi tra i candidati non sono sorti.

I risultati

Il voto anticipato è popolare in Finlandia e circa il 21% di tutti gli elettori registrati aveva già votato il 21 maggio, il che suggeriva che l’affluenza sarebbe stata circa la stessa del 2014. Alla fine l’affluenza al voto è leggermente aumentata rispetto al 2014 con un 42,7% di elettori che ha espresso il suo voto.

Quando sono stati annunciati i risultati del voto anticipato, sembrava che le aspettative sarebbero state largamente soddisfatte. Man mano che venivano contati i voti poi, si sono verificati alcuni sviluppi, ma il quadro generale è rimasto simile. Tre ore dopo la chiusura dei seggi elettorali, i risultati preliminari erano disponibili per l’intero paese. Alla fine, il risultato ha confermato le aspettative secondo cui il KOK sarebbe rimasto il primo partito: ha raccolto il 20,8% dei voti, ottenendo tre seggi. Tuttavia, ancora più positivi sono stati i verdi (VIHR), che sono diventati il secondo partito con il 16,0%, registrando un aumento pari a 6,7 punti rispetto al 2014 e ottenendo un secondo seggio. L’SDP ha anch’esso guadagnato voti rispetto al 2014 (+ 2,3 punti) e ha ricevuto il 14,6% di voti, conquistando due seggi, rimanendo tuttavia un po’ al di sotto del risultato delle elezioni nazionali. Il PS ha guadagnato un punto rispetto al 2014, ma il risultato del 13,8% è stato deludente considerando il 18% previsto prima delle elezioni. KESK è stato il principale sconfitto, avendo ottenuto solo il 13,5% dei voti: 6,1 punti in meno punti rispetto al 2014, cosa che è costata la perdita di un seggio a Strasburgo. Il VAS ha ottenuto il 6,9% dei voti e ha mantenuto il proprio seggio. Lo sviluppo più importante durante la serata è stato però l’aumento al 6,3% della percentuale dei voti dell’RKP, che ha scalato la lista per aggrapparsi al 13° seggio. La battaglia per il 14° seggio, il “Brexit-seat”, era molto ravvicinata e ha visto cambiare più volte il partito che avrebbe vinto il posto di riserva. Alla fine è andato ai Verdi, i quali otterranno un posto aggiuntivo quando la Brexit sarà completata, quello che la Finlandia otterrà in più nel Parlamento Europeo.

| Tab. 2 – Risultati delle elezioni 2019 per il Parlamento Europeo: Finlandia | ||||||||

| Partito | Gruppo Parlamentare | Voti (N) | Voti (%) | Seggi | Seggi in caso di Brexit | Voti (diff. Sul 2014) (%) | Seggi (diff. Sul 2014) | Seggi (diff. Sul 2014) in caso di Brexit |

| Partito della Coalizione Nazionale (KOK) | EPP | 380.106 | 20,8 | 3 | 3 | -1,8 | +0 | +0 |

| Lega verde (VIHR) | G-EFA | 292.512 | 16,0 | 2 | 3 | +6,7 | +1 | +2 |

| Partito Socialdemocratico (SDP) | S&D | 267.342 | 14,6 | 2 | 2 | +2,3 | +0 | +0 |

| Veri Finlandesi (PS) | ECR | 252.990 | 13,8 | 2 | 2 | +1,0 | +0 | +0 |

| Partito di Centro (KESK) | ALDE | 247.416 | 13,5 | 2 | 2 | -6,1 | -1 | -1 |

| Alleanza di Sinistra (VAS) | GUE-NGL | 125.749 | 6,9 | 1 | 1 | -2,4 | +0 | +0 |

| Partito Popolare Svedese (RKP) | ALDE | 116.033 | 6,3 | 1 | 1 | -0,4 | +0 | +0 |

| Cristiano-democratici (KD) | EPP | 89.166 | 4,9 | 0 | 0 | -0,4 | +0 | +0 |

| Altri | 57.485 | 3,1 | ||||||

| Totale | 1.828.799 | 100 | 13 | 14 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Affluenza al voto (%) | 42,7 | |||||||

| Soglia legale di sbarramento (%) | Nessuna | |||||||

Conclusioni

Le previsioni erano fosche sia in termini di affluenza che di risultati. Analizzato sotto questa luce, il risultato può essere considerato una cauta vittoria per la fazione pro-UE. Mentre un’affluenza del 42,7% non è certo impressionante, è però soddisfacente considerando il contesto e la vicinanza alle elezioni nazionali.

Inoltre, la prevista vittoria per le forze euroscettiche non si è concretizzata in Finlandia, dove i partiti di maggior successo hanno tutti sostenuto programmi pro-integrazione finalizzati ad assicurare una crescita economica e a combattere il cambiamento climatico. Sebbene il PS abbia aumentato i propri voti rispetto al 2014, questi non sono riusciti a fargli conquistare un seggio aggiuntivo; inoltre, ha chiaramente registrato una performance negativa rispetto alle previsioni della vigilia.

I risultati hanno replicato quelli delle elezioni nazionali nel senso che, anziché tre grandi partiti e numerosi piccoli piccoli, ora vi sono diversi partiti di medie dimensioni nella politica finlandese. In caso contrario, le elezioni europee 2019 sono state una delle rare occasioni in cui la maggior parte dei partiti ha trovato motivi per essere soddisfatti del risultato. Persino KESK, l’unico partito che ha perso un seggio, era contento che l’arretramento non fosse stata ancora più pronunciato.

L’ondata di sostegno europeo per i partiti verdi trova risonanza in Finlandia, dove il principale messaggio che emerge dagli elettori sembra essere quello che vede il Parlamento Europeo assumere un ruolo guida negli sforzi volti a combattere il cambiamento climatico.

Riferimenti bibliografici

De Lucia, F. (2019), ‘Elezioni in Finlandia, la sinistra cresce ma non vince’, Centro Italiano Studi Elettorali, disponibile presso: https://cise.luiss.it/cise/2019/04/17/elezioni-in-finlandia-la-sinistra-cresce-ma-non-vince/

De Vries, C. E. (2018), Euroscepticism and the Future of European Integration, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Mattila, M. (2003), ‘Why bother? Determinants of turnout in the European elections’, Electoral Studies, 22 (3), pp. 449-469.

Schmitt, H. e Toygür, I. (2016), ‘European Parliament Elections of May 2014: Driven by National Politics or EU Policy Making?’, Politics and Governance, 4 (1), pp. 167-181.

Von Schoultz, Å. (2018), ‘Electoral Systems in Context: Finland’, in E. S. Herron, R. J. Pekkanen e M. S. Shugart (a cura di), The Oxford Handbook of Electoral Systems, Oxford, Oxford University Press, pp. 601-626.