Traduzione di Irene Fratellini.

La campagna elettorale per le elezioni europee del 2019 nel Regno Unito ha aspettato l’ultimo minuto per partire, considerando anche che la partecipazione del paese alle elezioni non era in programma. Originariamente il Regno Unito avrebbe dovuto lasciare l’Unione Europea il 29 marzo, ma le estensioni dell’articolo 50 – il processo legale e politico per lasciare l’Unione Europea – di fine di marzo e di metà aprile hanno comportato la partecipazione del Regno Unito secondo il diritto dell’UE. Nonostante ciò, non prima del 7 maggio è stato ammesso dal primo ministro Theresa May che il Regno Unito avrebbe effettivamente partecipato alle elezioni europee del 23 maggio.

La Brexit ha introdotto una nuova dimensione tematica nel Regno Unito dopo il referendum UE del 2016 (Goodwin and Heath 2016a, 2016b, 2017). Una nuova linea di conflitto che taglia trasversalmente le tradizionali linee di conflitto politico: infatti sostenitori dell’uscita dall’UE ma anche della permanenza sono presenti sia nel partito conservatore attualmente al governo, che fra i laburisti, il principale partito di opposizione. Mentre la posizione ufficiale del partito conservatore è pro-Leave, ossia a sostegno all’uscita dall’UE, il partito laburista sotto la guida di Jeremy Corbyn è stato meno chiaro sulla sua posizione. Questa differenza tra i due partiti principali si era già distinta durante la campagna per le elezioni generali del Regno Unito del 2017 (Mellon et al., 2018, Vaccari et al., in corso di pubblicazione).

A causa della natura divisiva della questione europea, e soprattutto in vista della Brexit, i due principali partiti del Regno Unito hanno considerato problematica la partecipazione alle elezioni, ed entrambi di fatto avrebbero voluto evitare questo scenario. Con la Brexit sullo sfondo, le elezioni al Parlamento Europeo sono state comunemente considerate una proxy di un nuovo referendum sulla questione se lasciare o meno l’Unione Europea e, in caso affermativo, in che modo. Lo stesso dicasi per le elezioni comunali, tenutesi il 2 maggio nella maggior parte del paese, che ha visto i due partiti principali subire le “ripercussioni della Brexit” (Walker 2019). In queste elezioni locali, il Partito Conservatore guidato da Theresa May ha perso 1.330 seggi su 8.410. Inoltre, il Partito Laburista, il principale partito di opposizione guidato da Jeremy Corbyn, non è stato in grado di giovarsi della sconfitta del partito di governo e ha perso ben 84 consiglieri. I Liberal Democratici e i Verdi, contrari all’uscita dall’UE, d’altra parte, hanno inaspettatamente guadagnato 705 e 194 seggi, rispettivamente. È interessante notare come questo risultato a favore dei partiti pro-Unione sia stato interpretato tanto dal Partito Conservatore che dal Partito Laburista come un messaggio da parte dell’elettorato per “darsi da fare e portare a casa la Brexit”.

In vista delle elezioni europee del 23 maggio, due nuovi partiti sono entrati nell’agone politico. Nigel Farage, ex leader del Partito per l’Indipendenza del Regno Unito (UKIP), è infatti riapparso con il Partito della Brexit. Questo partito monotematico a favore di una Brexit senza accordo (che ha sostenitori anziché membri e non ha un vero programma politico) si è ben presto portato in testa nei sondaggi, grazie alla capacità di attrarre molti elettori delusi del Partito Conservatore. In realtà, rientrava nelle aspettative che lo stesso Partito Conservatore mettesse in scena la sua peggiore performance, date le crescenti turbolenze intestine, le voci sulle dimissioni di Theresa May da Primo Ministro,i cambiamenti nella leadership del partito e, infine, un quarto voto in Parlamento sull’accordo Brexit di Theresa May con l’UE.

Il secondo nuovo partito di orientamento moderato e contrario all’uscita dall’UE, Change UK – The Independent Group (CUK-TIG), si è invece venuto a formare da parlamentari fuoriusciti dal Partito Laburista e dal Partito Conservatore. A differenza del partito Brexit, questi non ha mai spiccato particolarmente: secondo le previsioni avrebbe dovuto ricevere una percentuale di voto a singola cifra. Oltre al Partito della Brexit, anche i Liberal Democratici e i Verdi erano attesi a risultati positivi nelle elezioni. Si prevedeva che entrambi i partiti avrebbero guadagnato voti da sostenitori del Partito Laburista, delusi dal fatto che né il partito né il suo leader Jeremy Corbyn si fossero espressi in modo inequivocabile per rimanere nell’Unione Europea.

Il 23 maggio, gli elettori di Gran Bretagna e Irlanda del Nord hanno eletto un totale di 73 deputati al Parlamento Europeo. Il Regno Unito è diviso in 12 regioni, in cui gli elettori eleggono tra 3 e 10 deputati al Parlamento Europeo a seconda delle dimensioni demografiche della regione. A differenza delle elezioni politiche, in cui un candidato è eletto in ciascuno dei 650 collegi uninominali del Regno Unito, utilizzando il sistema maggioritario a turno unico, le elezioni per il Parlamento Europeo si svolgono secondo un sistema proporzionale (Angelucci e Paparo 2019). La scheda in Gran Bretagna riporta partiti e nomi di candidati, e gli elettori selezionano un partito o un candidato indipendente. I seggi sono assegnati in modo proporzionale alla percentuale di voti espressi per i partiti (ma non a una persona in corsa per quel partito) o per i candidati indipendenti all’interno della regione. Al contrario, l’Irlanda del Nord usa il voto singolo trasferibile per eleggere i suoi 3 deputati e gli elettori ordinano quindi i diversi candidati in base alle loro preferenze.

Per quanto riguarda cittadini dell’UE residenti nel Regno Unito, essi non hanno goduto di una registrazione automatica per votare nelle elezioni europee e hanno dovuto registrarsi nuovamente a partire dal 7 maggio. 3million, un’organizzazione di cittadini UE residenti in Gran Bretagna che si batteva per mantenere i loro diritti esistenti dopo la Brexit, ha presentato una denuncia formale alla Commissione elettorale, temendo che molti cittadini dell’UE non avrebbero potuto votare alle elezioni. Secondo l’organizzazione, il processo strutturato in due fasi ha di fatto privato i cittadini europei dalla loro unica possibilità di esprimere un parere su Brexit (O’Carroll, 2019).

Dopo che si sono aperte le urne, il 23 maggio, l’hashtag #DeniedMyVote ha spopolato su Twitter, quando molti cittadini UE sono stati impossibilitati a votare. Infatti, una buona parte non era a conoscenza del fatto che avrebbe dovuto registrarsi nuovamente, mentre chi ci aveva provato non ha mai ricevuto il proprio modulo a causa di smarrimento, o, se arrivato, era fuori tempo massimo. La Commissione elettorale ha puntato il dito contro il governo britannico, affermando che la registrazione in occasione delle precedenti elezioni europee nel 2014 era scorsa in modo più limpido e comprensibile, sottolineando anche che il breve preavviso della partecipazione del Regno Unito a queste elezioni europee ha influito sul tempo a disposizione per sensibilizzare alla registrazione (Commissione elettorale, 2019).

Poiché la maggior parte dei paesi europei non ha votato fino a domenica 26 maggio, i voti delle elezioni di giovedì 23 maggio non sono stati conteggiati fino a quando non si sono chiusi i seggi negli altri Stati membri dell’UE. Nei giorni tra le elezioni e il conteggio dei, il Primo Ministro Theresa May ha annunciato il suo piano di dimettersi il 7 giugno, innescando una battaglia per la leadership all’interno del Partito Conservatore. Dopo settimane – se non mesi – di turbolenze, le sue dimissioni non sono state affatto una sorpresa e molti parlamentari conservatori hanno prontamente annunciato la loro candidatura alla guida del partito.

L’affluenza alle elezioni europee del 2019 nel Regno Unito è stata del 36,9%, in aumento di 1,5 punti percentuali rispetto al 2014. Come previsto, il nuovo Partito della Brexit ha fatto segnare il successo che ci si aspettava: raccogliendo il 32% del voto popolare, e conquistando così ben 28 eurodeputati – la delegazione più grande del Regno Unito. I Liberal Democratici ne escono come secondo partito, con il 20% dei voti e 15 deputati –14 in più rispetto al 2014. Non è una sorpresa che i LibDems abbiano vinto le elezioni nella Londra contraria alla Brexit. Il Partito dei Verdi ha aumentato di 4 il numero di seggi ottenuti rispetto alle elezioni precedenti, inviando un totale di 7 deputati a Strasburgo, avendo raccolto il 12,1% del voto popolare.

Sia i laburisti che i conservatori hanno subito un duro colpo in queste elezioni. Il Partito Laburista è arrivato al 3° posto con il 14,1% dei voti, in calo di 11,3 punti percentuali rispetto al 2014. Ora ha 10 eurodeputati, la metà di quelli di cui godeva prima del voto. Il Partito Conservatore ha ottenuto il 5° posto, con il 9,1% dei voti, la peggiore performance in un’elezione nazionale in quasi 200 anni. Ha perso 15 eurodeputati e attualmente ha 4 seggi al Parlamento Europeo.

Anche due partiti regionalisti britannici hanno vinto seggi al Parlamento Europeo. Il Partito Nazionalista Scozzese ha infatti ottenuto 3 seggi (1 in più rispetto al 2014), mentre il partito gallese Plaid Cymru ha mantenuto il proprio seggio. I tre seggi nordirlandesi sono andati allo Sinn Féin, al Partito Democratico Unionista e al Partito dell’Alleanza. Inoltre, per la prima volta nella storia, questa regione invierà 3 eurodeputati donna. Newcomer Change UK non ha vinto seggi, e l’UKIP ha perso tutti i suoi 24 seggi al Parlamento Europeo, dopo essere passato all’estrema destra sotto la guida di Gerard Batten.

| Tab. 1 – Risultati delle elezioni per il Parlamento Europeo del 2019: Regno Unito | ||||||

| Party | Gruppo parlamentare | Voti (N) | Voti (%) | Seggi | Variazione di voti dal 2014 (%) | Variazione di seggi dal 2014 |

| Partito della Brexit | EFD | 5248533 | 31,6 | 29 | +31,6 | +29 |

| Liberal Democratici | ALDE | 3367284 | 20,3 | 16 | +13,4 | +15 |

| Partito Laburista | S&D | 2347255 | 14,1 | 10 | -11,3 | -10 |

| Partito verde di Inghilterra e Galles | G-EFA | 2023380 | 12,1 | 7 | +4,2 | +4 |

| Partito Conservatore | ECR | 1512147 | 9,1 | 4 | -14,8 | -15 |

| Partito Nazionalista Scozzese | G-EFA | 594553 | 3,6 | 3 | +1,1 | +1 |

| Plaid Cymru | G-EFA | 163928 | 1,0 | 1 | +0,3 | |

| Sinn Féin | GUE-NGL | 126951 | 1 | |||

| Partito Unionista Democratico | NI | 124991 | 1 | |||

| Partito dell’Alleanza dell’Irlanda del Nord | ALDE | 105928 | 1 | |||

| Change UK | EPP | 571846 | 3,4 | 0 | +3,4 | |

| Partito per l’Indipendenza del Regno Unito | EFD/NI | 554463 | 3,3 | 0 | -24,2 | -24 |

| Partito Unionista dell’Ulster | ECR | 53052 | 0 | -1 | ||

| Totale | 16794311 | 100 | 73 | – | ||

| Affluenza (%) | 36,9 | |||||

| Soglia legale di sbarramento (%) | Nessuna | |||||

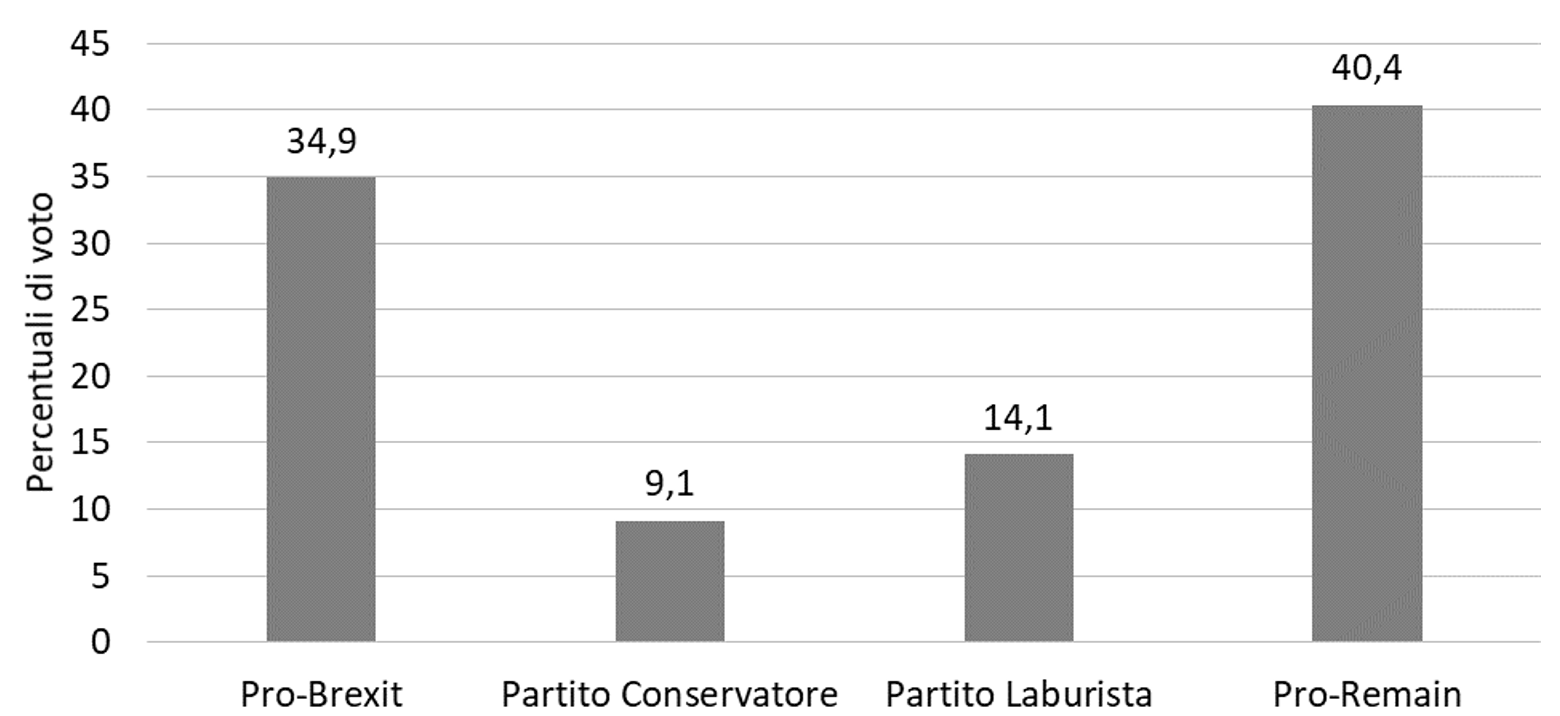

Mentre il Partito della Brexit ha raccolto il maggior numero di voti nelle elezioni, è chiaro che la Brexit rimane una questione altamente controversa nel Regno Unito. Confrontando i risultati elettorali dei partiti esplicitamente pro-Leave (Brexit Party e UKIP) e dei partiti esplicitamente pro-Remain (LibDems, Verdi, SNP, Plaid Cymru e Change UK), il bilancio sembra in qualche modo a favore dei partiti contrari all’uscita dall’UE, con una quota di voto totale del 40,4%. I partiti pro-Leave insieme hanno raccolto il 34,9% dei voti. L’ultima parola sulla Brexit non è stata ancora chiaramente pronunciata e la direzione che prenderà il Regno Unito nei prossimi mesi dipenderà in gran parte da chi diventerà il nuovo Primo Ministro.

Fig. 1 – Quote di voto per i partiti pro-Brexit[1] e pro-Remain[2]

Riferimenti bibliografici

Angelucci, D. e Paparo, A. (2019), ‘L’Europa al voto, ma con quali regole?’, Centro Italiano Studi Elettorali, disponibile presso: https://cise.luiss.it/cise/2019/05/22/leuropa-al-voto-ma-con-quali-regole/

Goodwin, M.J. e Heath, O. (2016a), ‘The 2016 referendum, Brexit and the left behind: an aggregate‐level analysis of the result’, The Political Quarterly, 87 (3), pp. 323-332.

Goodwin, M.J. e Heath, O. (2016b), ‘Brexit vote explained: poverty, low skills, and lack of opportunity’ Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Goodwin, M., e Heath, O. (2017), ‘UK 2017 General Election Examined: Income, Poverty and Brexit’, Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Mellon, J., Evans, G., Fieldhouse, E., Green, J. e Prosser, C. (2018), ‘Brexit or Corbyn? Campaign and Inter-Election Vote Switching in the 2017 UK General Election’, Parliamentary Affairs, 71 (4), pp. 719-737.

O’Carroll (2019). ‘Many EU citizens will be unable to vote in UK, campaigners warn.’ The Guardian. 21 May 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2019/may/21/european-elections-many-eu-citizens-will-be-unable-to-vote-in-uk-campaigners-warn

UK Electoral Commission (2019), ‘Electoral Commission statement regarding some EU citizens being unable to vote in the European Parliamentary Elections’, 23 maggio, disponibile presso: https://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/i-am-a/journalist/electoral-commission-media-centre/to-keep/electoral-commission-statement-regarding-eu-citizens-being-unable-to-vote-in-the-european-parliament-elections

Vaccari, C., Smets, K. e Heath, O. (in corso di pubblicazione), ‘The United Kingdom 2017 Election: Polarization in a Split Issue Space’, West European Politics.

Walker, P. (2019), ‘Tories and Labour suffer Brexit backlash as Lib Dems gain in local elections’, The Guardian, 3 maggio, dispobile presso: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2019/may/03/liberal-democrats-conservatives-labour-local-elections-brexit-2019

[1] Partito della Brexit e UKIP.

[2] Liberal Democratici, Verdi, SNP, Plaid Cymru e Change UK.