Traduzione di Giorgia Ramazzotti.

L’ottava elezione per il Parlamento Europeo in Spagna ha segnato la fine di un ciclo elettorale iniziato un mese prima (il 26 Aprile 2019) con le elezioni legislative in cui il Partito Socialista (PSOE) al governo alla vigilia ha vinto la pluralità dei seggi. Tuttavia, al momento delle europee, ancora non si è raggiunto un un accordo parlamentare per eleggere un nuovo governo nazionale, dal momento che la maggior parte dei partiti intendeva rimandare la decisione a dopo tale tornata. Innanzitutto, durante la campagna per le europee, i politici catalani che avevano organizzato il referendum per l’indipendenza nell’ottobre del 2017 e che competevano come candidati sia alle politiche che alle europee, sono stati tenuti in carcere in attesa che venissero processati. Tutti questi elementi hanno contribuito alla nazionalizzazione dei contenuti della campagna elettorale che ha preceduto le elezioni europee.

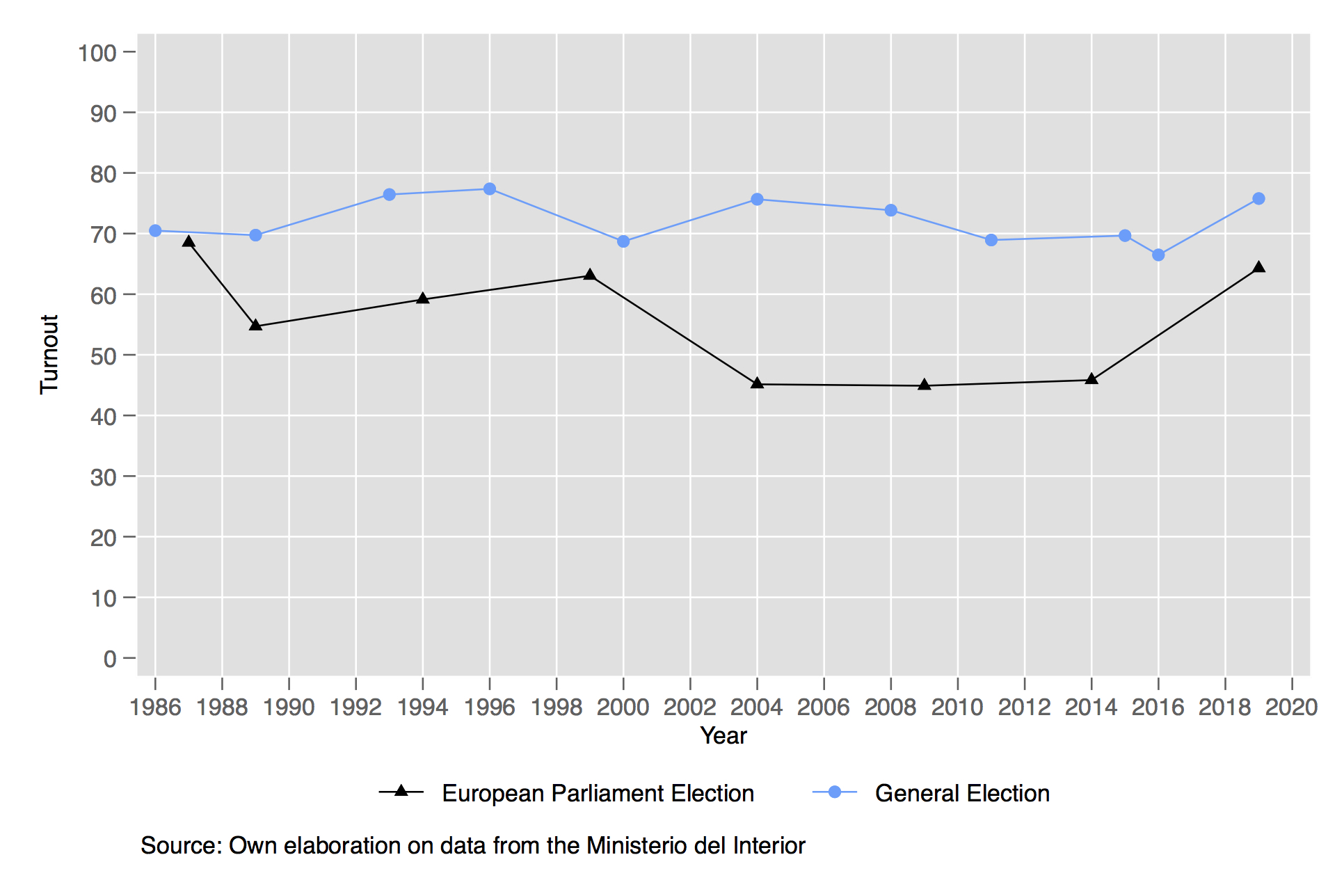

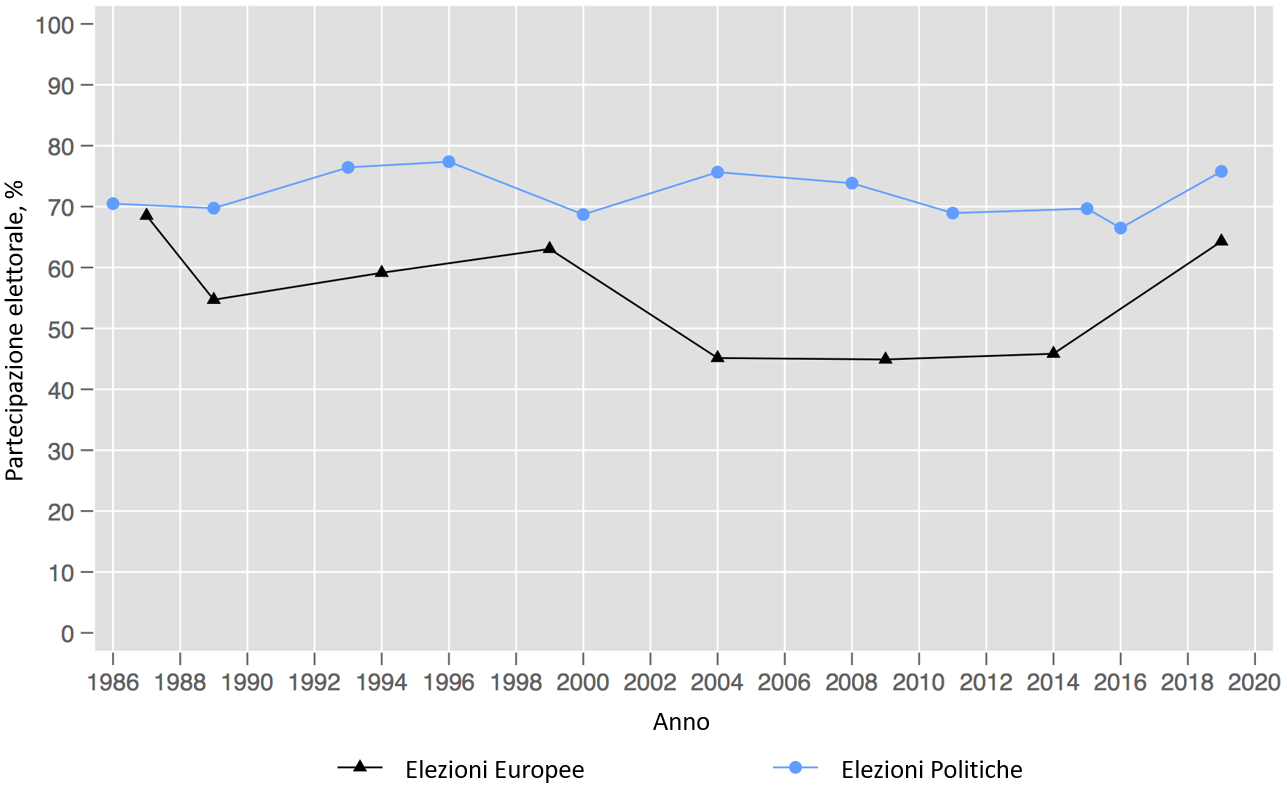

Probabilmente il fatto più rilevante delle europee 2019 è che, per la prima volta dal 1987, queste si sono tenute nello stesso giorno delle elezioni regionali (in dodici delle diciassette regioni) e delle elezioni municipali in tutte i comuni spagnoli. La fatica elettorale dovuta alla sequenza di elezioni in un breve periodo avrebbe potuto aver scoraggiato la partecipazione. Tuttavia, rispetto alle europee del 2014, la partecipazione è cresciuta di più di 20 punti percentuali, suggerendo un ‘effetto contagio’ guidato da alti livelli di mobilitazione per le elezioni locali e regionali. Durante la campagna elettorale, inoltre, le stime prevedevano corse molto combattute in molte municipalità e regioni. L’incertezza sui risultati delle elezioni ha probabilmente ulteriormente contribuito alla crescita dei livelli di partecipazione.

La campagna elettorale

Il periodo precedente il voto è stato dominato da due tematiche. Prima di tutto, subito dopo le politiche, la maggior parte dei partiti ed esperti si è focalizzata sull’interpretazione delle consequenze dei risultati, prestando particolare attenzione agli accodi di coalizione che il partito vincitore (PSOE) avrebbe potuto stringere per formare un nuovo governo. Anche i media hanno dato molta attenzione alla sconfitta del tradizionale partito di destra, il Partido Populare (PP), che ha perso metà dei suoi seggi in Parlamento. Questo ha generato una insolita e sostanziale frammentazione del voto di destra, che si è diviso tra il PP, il nuovo avversario di estrema destra VOX (che ha ottenuto un totale di 24 seggi in Parlamento) e Ciudadanos (un partito di centrodestra).

In secondo luogo, quattro settimane prima delle europee, i media hanno dato particolare attenzione anche al fatto che i politici catalani che erano o in carcere o all’estero per evitare il processo, stessero correndo come candidati alle europee nelle coalizioni ‘Ahora Republicas’ e ‘Lliures per Europa’. Inizialmente la Commissione per le Elezioni Nazionali ha impedito ai candidati che erano all’estero (come l’ex presidente catalano Carles Puigdemont) di competere. Tuttavia, dopo un appello da parte di questi politici, le Corti hanno giudicato che potessero concorrere alle elezioni. Ad ogni modo, al momento della stesura di questo articolo, ancora non è chiaro se questi politici possano effettivamente diventare membri del Parlamento Europeo, dal momento che questo gli richiederebbe di attraversare a Spagna, dove potrebbero essere arrestati.

In Spagna, così come in altri paesi, è solito che per le campagne delle europee ci si focalizzi sui temi nazionali (Font e Torcal 2012). Le elezioni del 2019 non hanno fatto eccezione a questa tendenza, che è stata rinforzata dalla coincidenza di queste elezioni con le elezioni regionali e comunali. L’incertezza sui risultati in alcune comuni importanti, come Madrid o Barcellona, ha portato un’attenzione sproporzionata a queste consultazioni, a svantaggio delle europee. Ad esempio, il leader del PP Pablo Casado ha caratterizzato le elezioni municipali, regionali ed europee come un secondo round delle politiche, cosa che ha dato la possibilità al PP di migliorare il cattivo risultato ottenuto in quelle elezioni. Inoltre, il PP e Ciudadanos, che sono finiti al secondo e terzo posto alle politiche con percentuali di voti molto simili (16,7% e 15,9% rispettivamente), hanno visto queste elezioni come una opportunità per determinare quale di questi due partiti avrebbe guidato l’opposizione conservatrice contro il nuovo governo PSOE.

Ad ogni modo, i media spagnoli hanno anche caratterizzato le europee come un plebiscito sul futuro dell’integrazione europea, per via della minaccia posta dalla possibile ondata dei partiti euroscettici. In questo contesto, e per la prima volta, i nove candidati alle europee dei principali partiti e coalizioni (vedi Tabella 1) hanno partecipato ad un dibattito trasmesso dal servizio televisivo pubblico spagnolo in prima serata. Tuttavia, sebbene i candidati abbiano anche dibattuto su temi relativi all’UE (come la rilevanza delle politiche UE sull’immigrazione, o le sfide poste dal cambiamento climatico), la discussione è stata chiaramente dominata da questioni interne, soprattutto la situazione in Catalogna e l’accesa polarizzazione attorno alle possibili soluzioni a tale problema.

Con l’eccezione di VOX, i programmi elettorali dei principali partiti (PSOE, PP, Ciudadanos, Unidas Podemos) condividono una visione positiva del processo di integrazione europea e propongono nuove politiche che rafforzerebbero l’UE, come un maggiore coordinamento in materia fiscale e delle politiche migratorie. Infatti, mentre ciascun partito enfatizza diverse tematiche, le proposte sono più simili tra loro di quanto non siano i loro programmi a livello nazionale (Abellán 2019). Il nuovo partito di estrema destra VOX rappresenta un’eccezione a questa tendenza generale. VOX auspica la protezione della sovranità nazionale e il ritorno alle origini (pre-Maastricht) del processo di integrazione. Possiamo pertanto caratterizzare VOX come un partito euroscettico moderato dal momento che non ha particolari obiezioni contro l’appartenzenza all’UE, ma si oppone chiaramente ad una integrazione ulteriore e, in alcune aree di policy, propugna la devoluzione di competenze alle istitutzioni nazionali (Taggart e Szczerbiak 2002).

I risultati

La Figura 1 riassume l’affluenza alle elezioni europee e nazionali in Spagna per il periodo 1986-2019. Le europee 2019 hanno visto un significativo picco di partecipazione, che è aumentata dal 45,8% del 2014 al 64,5% nel 2019. La concomitanza con le elezioni regionali e comunali ha indubbiamente contribuito a questo slittamento verso l’alto. Tuttavia, la partecipazione è stata leggermente più bassa di quella delle europee del 1987, che furono anch’esse tenuta lo stesso giorno delle elezioni comunali e regionali. Ciononostante, bisogna notare che nel 1987 era anche la prima volta che gli spagnoli votavano per eleggere i propri rappresentanti al Parlamento Europeo, cosa che potrebbe aver contribuito all’alto tasso di affuenza. Ad ogni modo, la partecipazine alle europee 2019 è stata più bassa anche di quella alle precedenti elezioni nazionali tenutesi soltanto un mese prima, confermando il carattere di ‘secondo ordine’ di queste elezioni in Spagna (Reif and Schmitt 1980).

Fig. 1 – La partecipazione elettorale in Spagna

La Tabella 1 riassume i risultati delle europee 2019 i Spagna. Il chiaro vincitore di questa elezione è stato il partito socialista (PSOE) che è stato capace di capitalizzare sulla recente vittoria alle politiche: ha ottenuto un totale di 20 seggi, e 3,7 milioni di voti in più rispetto alle precedenti europee. A ben guardare, il suo risultato (32,6%) è stato persino più alto che alle recenti politiche, dove il 28,7% degli elettori ha votato i socialisti. Al contrario, il PP ha perso molto terreno in queste elezioni rispetto alle europee 2014: il risultato del PP è stato 6 punti percentuali più basso e il partito ha perso quattro seggi nell’EP. Tuttavia, il PP è riuscito ad ottenere una percentuale di voto più alta rispetto alle recenti elezioni politiche.

| Partito | Gruppo parlamentare | Voti (VA) | Voti (%) | Seggi | Differenza di voti dal 2014 (PP) | Differenza di seggi dal 2014 |

| Partito Socialista (PSOE) | S&D | 7.359.617 | 32,6 | 20 | +9,5 | +6 |

| Partito Popolare (PP) | EPP | 4.510.193 | 20,0 | 12 | -6,1 | -4 |

| Ciudadanos | ALDE | 2.726.642 | 12,1 | 7 | +8,9 | +5 |

| Podemos-IU[1] | GUE/NGL & G-EFA | 2.252.378 | 10,0 | 6 | -8,0 | -5 |

| VOX | NI | 1.388.681 | 6,1 | 3 | +4,6 | +3 |

| Repubbliche ora[2] | G-EFA | 1.257.484 | 5,6 | 3 | -0,5 | +0 |

| Junts | NI | 1.025.411 | 4,5 | 2 | +4,5 | +2 |

| Coalizione per un’Europa solidale (CEUS) | ALDE | 633.265 | 2,8 | 1 | +2,8 | +1 |

| Compromesso per l’Europa (CPE)[3] | 296.091 | 1,3 | 0 | -0,6 | -1 | |

| PACMA | 294.657 | 1,3 | 0 | +0,2 | +0 | |

| Coalizione per l’Europa (CEU) | ALDE | 0 | 0,0 | -5,4 | -3 | |

| Unione per il Progresso e la Democrazia (UPyD) | ALDE | 0 | 0,0 | 0 | -6,5 | -4 |

| Altri | 859.479 | 3,8 | 0 | |||

| Totale | 22.603.898 | 100 | +0 | |||

| Affluenza (%) | 64,3 | |||||

| Soglia legale di sbarramento (%) | Nessuna | |||||

D’altra parte, mentre i risultati di Ciudadanos sono migliorati chiaramente rispetto alle precedenti europee, il partito si è comportato peggio che alle ultime elezioni politiche, e ha fallito il tentativo di diventare il partito dominante della destra spagnola. Anche nel caso di Podemos-IU i risultati sono stati negativi, dal momento che hanno perso 8 punti percentuali e cinque seggi a Strasburgo rispetto al 2014. Nel caso di VOX, il partito di estrema destra sarà rappresentato al Parlamento Europeo per la prima volta, con tre seggi. Tuttavia, il suo risultato percentuale alle europee è stato inferiore di quattro punti percentuali rispetto alle precedenti politiche (10,3%).

Oltre a questi partiti di estensione nazionale, il sistema partitico spagnolo è caratterizzato dalla presenza di forti partiti a base regionale. Siccome la natura uni-distrettuale del sistema elettorale dell’EPE penalizza i piccoli partiti a base regionale, questi partiti solitamente concorono con partiti di altre regioni. Questo è per esempio il caso della coalizione ‘Repubblica adesso’ che, sotto la leadership del leader catalano in arresto Oriol Junquerase e in coalizione con i partitinazionalisti di altre regioni, ha ottenuto treseggi all’EP. Similarmente, la ‘Coalizione per un’Europa Solidale’ guidata dai nazionalisti baschi di centro-destra ha vinto due seggi. Infine, la coalizione di cetro-destra ‘Insieme’, guidata dall’ex presidente catalano Carles Puigdemont, ha vinto due seggi.

Conclusioni

Le europee 2019 hanno segnato la fine di un ciclo elettorale in Spagna e sono state il chiaro riflesso del clima elettorale al livello nazionale. Il voto è stato altamente frammentato sia a sinistra che a destra, sebbene i due partiti tradizionali (PSOE e PP) abbiano finito per dominare i due versanti. C’è stata una leggera predominanza della sinistra, insieme a un notevole successo per i partiti nazionalisti – che hanno ricevuto approssimativamente il 13% dei voti. Il partito di estrema destra VOX ha disatteso le aspettative, ma è comunque riuscito ad entrare l’EP per la prima volta.

Gli elettori spagnoli sembrano ancora mancare di uno spirito genuinamente europeo (Molina, 2019). A differenza dell’Italia, il Regno Unito o la Francia, e nonostante i recenti cambiamenti nel sistema partitico spagnolo verso il multipartitismo, i partiti politici sembrano non voler politicizzare il processo di integrazione europea dal lato dell’offerta. Dal lato della domanda, i cittadini spagnoli sembrano mancare di connessione alla dimensione europea: una sfera politica spesso percepita dai cittadini come troppo remota e distaccata dai problemi quotidiani. Ancora una volta, la campagna elettorale e i risultati delle europee 2019 in Spagna suggeriscono che le figure politiche più importanti attribuiscono scarsa rilevanza alle elezioni per Strasburgo.

Riferimenti bibliografici

Abellán, Lucía, (2019), ‘La urna europea queda en tercer plano para España’, El País, May 26.

Font, Joan e Torcal, Mariano (2012), Elecciones europeas 2009, Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.

Molina, Ignacio (2019), ‘Un voto europeísta muy poco europeizado’, El País, May 27

Reif, Karlheinz e Schmitt, Hermann (1980), ‘Nine Second-Order National Elections – a Conceptual Framework for the Analysis of European Election Results’, European Journal of Political Research 8 (1), pp. 3–44.

Taggart, Paul e Szczerbiak, Aleks (2002), ‘The Party Politics of Euroscepticism in EU Member and Candidate States’, SEI Working Paper, 51.

[1] Per calcolare la variazione di voti e seggi consideriamo la differenza rispetto alle coalizioni “La Izquierda Plural” e Podemos nelle europee 2014.

[2] Per calcolare la variazione di voti e seggi consideriamo la differenza rispetto alle coalizioni ‘Sinistra per il diritto di scegliere’ (EDPP) e ‘Il popolo sceglie’ (LPD) alle europee 2014.

[3] Per calcolare la variazione di voti e seggi consideriamo la differenza rispetto alla coalizione “Primavera Europea” alle europee 2014.