Nina Liljeqvist

The Swedish Social Democratic Party (S) showed in last week’s general election how to win, without being much of a winner. The party did receive the most votes (31 %), and together with the other two opposition parties on the left – the Left party (V) (5,7 %) and the Greens (Mp) (6,9 %) – the red-green parties garnered 43,6 percent of the vote share. According to the final results just released by the election authority, this corresponds to 159 seats in parliament, which is short of the 175 needed for a parliamentary majority. The red-green block beat the four-party centre-right coalition by just over four percentage points. The resigning government coalition, the Alliance, consisting of the Moderates (M) (23,3 %), the Centre Party (C) (6,1 %), the Liberals (Fp) (5,4 %), and the Christian Democrats (4,6 %) received 39,4 percent of the votes, or 141 seats. Add to this the advance of far-right party Sweden Democrats (SD). With 12,9 percent of the votes and 49 seats, SD emerges as the third largest party in parliament and thereby also the absolute holder of the balance of power. As a result, the task of forming a government for S party leader Stefan Löfven may be described as unenviable at best.

From the campaign to the results

It seems to be a natural law in political science that the third term for the incumbent is tough to win. The centre-right coalition managed to form a majority when it first entered the political arena in 2006, and was later reduced to a minority government in 2010. Come 2014, the coalition parties found themselves fighting against public dissatisfaction with a number of welfare institutions, including but not limited to education and health care. First and foremost, voters punished the party of former PM Fredrik Reinfeldt and finance minister Anders Borg, as support for the Moderates declined by almost seven percentage points vis-à-vis the 2010 election. As the preliminary election results came in, Reinfeldt immediately handed in his resignation from office and also announced his withdrawal from the party in a few months. Who will take his place is still uncertain. Perhaps less upsetting, but the results were also negative for M’s three coalition partners Fp (-2 pp), Kd (-1 pp) and C (-0,4 pp). In other words, the centre-right block has lost over ten percentage points in support, but disappointed voters have not turned to new government members S and Mp.

Like most socialist parties around Europe, the Swedish Social Democrats have in recent years struggled with falling support and a decreasing number of party members. The party has also suffered from a turbulent internal situation, especially a streak of short-lived party leaders with much more long-lived faux pas. New party leader Stefan Löfven, former welder and union negotiator, has promised increased spending on schools and hospitals by raising taxes, positions seemingly well-received by the voters. However, the 31 percent vote share he achieved is nothing short of a disappointment. As party support has only grown by 0,4 pp, the vote share is quite a bit from the 35 percent the party had aimed for, not to mention the 45 percent support enjoyed during its heydays. Government partner the Greens is also not advancing with the electorate. Despite its immense success in the European Parliament election just a few months ago[1], Mp in fact decreased in support by 0,5 pp from their 2010 results.

The red-green win is, in other words, a win with rather muted cheers. They won not because they performed well in the campaign, but rather, because the centre-right did worse. Although the government coalition and Reinfeldt will resign, it is not with ease that Löfven will take his place. Throughout the campaign, Löfven has remained agnostic with regard to government formation. While the Left Party (V) never was much of government material – earlier this year V leader Jonas Sjöstedt gave Löfven the ultimatum to ban companies making a profit from tax-subsidised welfare – Löfven’s dismissal of inviting the party into government the very day after the election came somewhat as a surprise. It is a surprise since Löfven’s list of allies grows thin. Could-have-been side-kick Feminist Initiative (Fi) (3,1 %) is not an option as it fell short of the finish line, the 4-per cent-threshold. V, in turn, is extremely unhappy with Löfven’s post-election rejection. V will most probably regard the Social Democratic alternative as the lesser evil in this situation and support its budget, but even so, this is not enough to get a red-green budget passed in parliament. First and foremost, it is not enough to keep out the real winner of this election, far-right party Sweden Democrats (SD).

Nationalist party Sweden Democrats more than doubled support received in the 2010 election. Garnering a current 12,9 per cent of the vote share, the party emerges as the third largest party in parliament and thereby becomes the absolute holder of the balance of power. The party entered the riksdag for the first time in 2010 and has steadily climbed the opinion polls ever since. With such electoral success, the party will probably claim a position of deputy speaker, chairmanship in the parliamentary committees, etc. Time will tell if this may propel the party to become a party like any other. Throughout its first term in parliament, the other seven parliamentary parties ostracized the SD. This took place while SD voted in line with M about 70 percent of the time during the last parliamentary session. All remaining parties refuse to cooperate with SD due to its harsh stance on immigration and asylum. Sweden is unique in this regard, at least in the Nordic context, as nationalist parties have become more or less accepted in neighbouring countries. The Danish People’s Party has served as a support party of a minority government in Denmark, the Finns Party have been included in government negotiations in Finland, and the Progress Party formed a government last year with the Conservatives in Norway. [2] SD’s continuous surge in support raises the question of how long the established parties may insist in keeping it at an arm’s distance, and, what effect this strategy will have on SD support. Surely, parties can freely chose with whom to cooperate, and consequently whom to ostracize, but what range of options is possible in the rather cemented political arena that Swedish block politics have become?

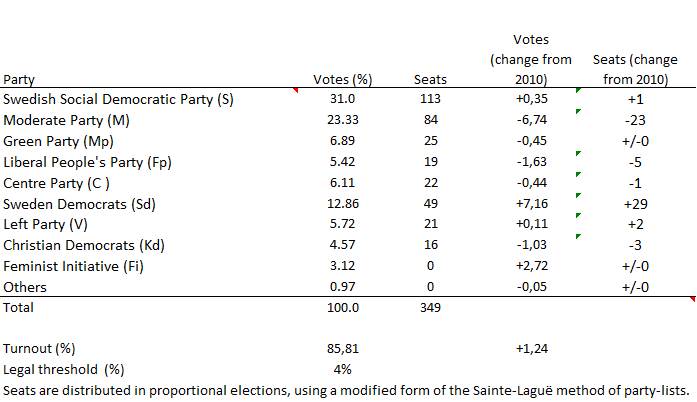

Table 1 – Results of the 2014 Swedish parliamentary elections

Where to from here?

The clock is ticking for Löfven to form a government and proceed with budgetary negotiations. By mid-November at the very latest, Löfven should present a budget before parliament, and at the moment he does not even know with whom to work this budget out with. Not even talks with the one given coalition partner, Mp, is going to be straightforward. Throughout the campaign, Löfven shunned all talk of what a red-green government would look like, how portfolios would be distributed and on what issues cooperation with centre-right parties could be possible, come the situation that the red-green block would not get a parliamentary majority. Löfven’s mantra of “let’s wait and see until after the election”, perhaps went down with the voters, but he is sweating that strategy now. Mp is neither in a very admirable situation. The list of issues on which the two parties differ is long and includes at least green taxes, nuclear energy, migration, transportation, and defence. Most of these issues are affairs of the heart for green voters, but history has shown that Mp usually draws the shortest straw when in disagreement with S.

Apart from Mp, Löfven has met with party leaders of the Alliance over the course of the last week to discuss possible areas of cooperation. The two small parties at the centre, the Liberals and the Centre Party, are of particular interest. In order to rob SD of its hold over the balance of power, Löfven needs to find an agreement with both. To do this he needs to be willing to compromise quite generously, not least on taxes, and S’s recently suggested trainee programme for young unemployed, which was met with great scepticism by the Alliance. Yet such compromise is the most probable scenario for the coming months. Despite all this uncertainty, talk of re-election is very unlikely. Pragmatism usually prevails in Swedish politics and agreement across the two blocks will sooner or later come about. Such agreement is common concerning certain issues, for instance regarding free schools.

The two blocks are not that pragmatic, however, that they would opt for some kind of grand coalition, consisting of the red-greens, Fp and C. Löfven raised the possibility during the campaign, but the aggrieved centre-right block maintains that they much prefer the role of a watchful opposition that they now have been given. The electorate has a much more practical view on the matter. Recent opinion data reveal that 52 percent of the general public now wish to see a government consisting of parties from both the red-green and centre-right block. Only a week ago, 13 percent of voters wanted to see such a type of hung parliament which signal a drastic change in the mind of the median voter.[3] Such a change in the mind of the median member of parliament appears unlikely.

_______________________

Nina Liljeqvist is a PhD researcher in political science at the European University Institute, Florence, Italy and a research fellow at the Swedish parliament for the parliamentary session 2014/15. Her research interests lie in the area of comparative politics, and more specifically in representative democracy, European integration, and Nordic politics.

[1] Liljeqvist, Nina (2014) Svezia: la fuga dai grandi partiti, in Le Elezioni Europee 2014, Lorenzo De Sio, Vincenzo Emanuele e Nicola Maggini (eds.) /cise/2014/05/28/svezia-la-fuga-dai-grandi-partiti/

[2] Nina Liljeqvist and Kristian Voss (2012) What can other far-right parties tell us about the Sweden Democrats?, The Local, published 27 Nov 2012. https://www.thelocal.se/20121127/44694

[3] SVT News “Väljarna vill ha blocköverskridande regering “, published 19 September 2014: https://www.svt.se/nyheter/val2014/valjarna-vill-se-blockoverskridande-regering