The campaign for the 2019 European Parliamentary election in the United Kingdom did not kick off until the last moment as the country’s government had not planned to take part in the election. The UK was originally scheduled to leave the European Union on the 29th of March, but extensions of Article 50 – the legal and political process for leaving the European Union – in late March and mid-April meant that the UK had to participate in the European Parliamentary elections under EU law. Despite this, it was not until the 7th of May that UK Prime Minister Theresa May conceded that the UK would indeed take part in the European election on the 23rd of May.

Brexit introduced a new issue dimension in the UK after the 2016 EU referendum (Goodwin and Heath 2016a, 2016b, 2017). Cutting across the traditional lines of political conflict, both Remainers and Leavers can be found among supporters and Members of Parliament of the incumbent Conservative Party and Labour, the main opposition party. Whilst the Conservative Party’s official stance is pro-Leave, the Labour Party under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn has been less clear on its position. This difference between the two main parties was also visible during the campaign for the 2017 UK General Election (Mellon et al. 2018, Vaccari et al. forthcoming).

Because of the divisive nature of the European issue, the UK’s two main parties considered holding EU elections in the run-up to Brexit problematic and both parties were eager to avoid this scenario. Against the backdrop of Brexit, the elections to the European Parliament were commonly considered a proxy for a new referendum on the question whether or not to leave the European Union, and if so how. This was also true for the local elections held on the 2nd of May in most of England, which saw the two main parties suffer a ‘Brexit backlash’ (Walker 2019). In these local elections, the Conservative Party led by Theresa May lost 1,330 out of 8,410 seats. Labour, the main opposition party led by Jeremy Corbyn, was not able to gain from the incumbent party’s defeat and lost 84 councillors. The pro-Remain Liberal Democrats and Greens, on the other hand, made unexpectedly large gains of 705 and 194 seats respectively. Curiously, this result in favour of pro-Remain parties was interpreted by both the Conservative Party and Labour as a message from the electorate to ‘get on and deliver Brexit’.

For the European elections on the 23rd of May, two new parties entered the political landscape. Nigel Farage, former leader of the right-wing UK Independence Party (UKIP), made a re-appearance with the Brexit Party. The one-issue party in favour of a no-deal Brexit, which has supporters instead of members and did not have a party manifesto, soon led the polls as many disappointed Conservative Party supporters were expected to switch allegiance to the Brexit Party. That very same Conservative Party was expected to see its worst ever performance amidst increasing turmoil within the Conservative Party, talks about Theresa May’s resignation as Prime Minister, changes in the party leadership, and a fourth vote in Parliament on Theresa May’s Brexit deal with the EU.

The second new party, the centrist and pro-Remain Change UK – The Independent Group (CUK-TIG), was formed by MPs who resigned from the Labour Party and the Conservative Party. Unlike the Brexit Party, it never gained much momentum and was expected to receive a percentage of the popular vote in the single digits. Besides the Brexit Party, the Liberal Democrats and the Greens were expected to fare well in the election. Both parties were predicted to gain votes from pro-Remain Labour supporters disappointed by the fact that neither the party nor its leader Jeremy Corbyn ever unequivocally spoke out in favour of remaining in the European Union.

On the 23rd of May voters in Great Britain and Ireland elected a total of 73 Members of European Parliament (MEPs). The UK is divided into 12 regions, in which voters elect between 3 and 10 MEPs depending on the population size of the region. Unlike national elections where one candidate is elected in each of the UK’s 650 constituencies using the first-past-the-post system, the elections for the European Parliament are held under a proportional system. The ballot in Great Britain features parties and names of candidates, and voters either select a party or an independent candidate. Seats are allocated proportionally to the share of votes cast for a party (but not an individual running for that party) or an independent candidate. Seats are allocated proportionally to the share of votes cast for each party or individual independent candidate in the region. Northern Ireland, on the other hand, uses Single Transferable Vote (STV) to elect its 3 MEPs and voters rank candidates according to their preference.

EU citizens living in the UK were not automatically registered to vote in the European Election and had to re-register by the 7th of May. The 3million, an organisation of EU citizens in the UK campaigning for them to retain their existing rights after Brexit, made a formal complaint to the Electoral Commission amid fears that many EU citizens would not be able to vote in the election. It argued that the two-step process practically deprived EU citizens from their only chance to voice an opinion on Brexit (O’Carroll, 2019).

After the polls opened on the 23rd of May the hashtag #DeniedMyVote soon trended on Twitter as many EU nationals were indeed not able to vote in the UK election to the European Parliament. Some EU citizens had not been aware they had to re-register, others had tried but their registration form was received too late or had gotten lost. The Electoral Commission pointed the finger to the UK Government, saying that it had already made a case for making registration easier in 2014 and that the short notice of the UK’s participation in the European elections impacted on the time available to raise awareness of the rules for registration (Electoral Commission, 2019).

As most European countries did not vote until Sunday the 26th of May, votes from the election on Thursday the 23rd of May were not counted until polls in other EU Member States were about to close. The days between the election and the counting of the votes saw Prime Minister Theresa May announcing her plan to resign on the 7th of June, triggering a leadership contest within the Conservative Party. After weeks – if not months – of turmoil, her resignation was not at all a surprise and many Conservative MPs soon announced their candidacy for the leadership of the party.

Turnout in the 2019 UK European Parliamentary election was 36,9%, up 1,5 percentage points in comparison to 2014. As expected, the new Brexit Party did well. It won 32% of the popular vote, got to send 28 MEPs to Brussels, and was the largest party in nine out of twelve UK regions. The Liberal Democrats were the second largest party with 20% of the vote and 15 MEPs (up 14 in comparison to 2014). Not surprisingly, the LibDems topped the polls in pro-Remain London. The Green Party increased its number of MEPs by 4, sending a total of 7 people to Brussels and garnering 12,1% of the popular vote.

Both Labour and the Conservatives were punished in the election. Labour placed 3rd with 14,1% of the vote, down 11,3 percentage points in comparison to 2014. It now has 10 MEPs, half of the number it had previously. The Conservative Party placed 5th with 9,1% of the vote – its worst performance in a national election in nearly 200 years. It lost 15 MEPs and currently has 4 seats in the European Parliament.

The two regional parties in Great Britain also won seats in the European Parliament. The Scottish National Party (SNP) garnered 3 seats (up 1 in comparison to 2014) and Welsh party Plaid Cymru kept its one seat. The three Northern Irish seats went to Sinn Féin, the Democratic Unionist Party and the Alliance Party, making it the first time in history that the region would send 3 female MEPs to Brussels. Newcomer Change UK did not win any seats, and UKIP lost all of its 24 seats in the European Parliament after shifting to the far-right under the leadership of Gerard Batten.

| Table 1 – Results of the 2019 European Parliament elections – United Kingdom | ||||||

| Party | EP Group | Votes (N) | Votes (%) | Seats | Votes change from 2014 (%) | Seats change from 2014 |

| The Brexit Party | EFD | 5248533 | 31.6 | 29 | +31.6 | +29 |

| Liberal Democrat | ALDE | 3367284 | 20.3 | 16 | +13.4 | +15 |

| Labour | S&D | 2347255 | 14.1 | 10 | -11.3 | -10 |

| Green | G-EFA | 2023380 | 12.1 | 7 | +4.2 | +4 |

| Conservative | ECR | 1512147 | 9.1 | 4 | -14.8 | -15 |

| Scottish National Party | G-EFA | 594553 | 3.6 | 3 | +1.1 | +1 |

| Plaid Cymru | G-EFA | 163928 | 1.0 | 1 | +0.3 | |

| Sinn Féin | GUE-NGL | 126951 | 1 | |||

| Democratic Unionist Party | NI | 124991 | 1 | |||

| Alliance Party | ALDE | 105928 | 1 | |||

| Change UK | EPP | 571846 | 3.4 | 0 | +3.4 | |

| UK Independence Party | EFD/NI | 554463 | 3.3 | 0 | -24.2 | -24 |

| Ulster Unionist Party | ECR | 53052 | 0 | -1 | ||

| Total | 16794311 | 100 | 73 | – | ||

| Turnout (%) | 36.9 | |||||

| Legal threshold for obtaining MEPs (%) | none | |||||

| Vote share figures do not include Northern Ireland as it has a separate electoral system to the rest of the UK. Vote totals for Northern Ireland are first preferences only. For parties running in both Northern Ireland and Great Britain, the vote share is just for England, Scotland and Wales, but the vote total is the sum of all GB votes plus the first preference votes in Northern Ireland. |

||||||

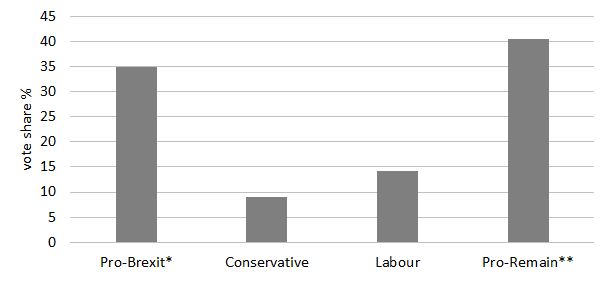

Whilst the Brexit Party garnered the largest vote share in the election, it is clear that Brexit remains a highly divisive issue in the UK. Comparing the vote shares of the explicitly pro-Leave parties (the Brexit Party and UKIP) and the explicitly pro-Remain parties (the LibDems, Green Party, the SNP, Plaid Cymru and Change UK), the balance seems somewhat in favour of the pro-Remain parties with a total vote share of 40,4%. The pro-Leave parties together garnered 34,9% of the vote. The last word on Brexit has clearly not yet been said and the direction the UK takes in the next months will largely depend on who becomes the new Prime Minister.

| Table 2 – Vote shares of pro-Brexit and pro-Remain parties | ||||

| Pro-Brexit* | 34.9 | |||

| Conservative | 9.1 | |||

| Labour | 14.1 | |||

| Pro-Remain** | 40.4 | |||

| Note: * The Brexit Party and UKIP; **LibDems, Greens, SNP, Plaid Cymru and Change UK |

References

Electoral Commission (2019). Electoral Commission statement regarding some EU citizens being unable to vote in the European Parliamentary Elections. UK Electoral Commission. 23 May 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/i-am-a/journalist/electoral-commission-media-centre/to-keep/electoral-commission-statement-regarding-eu-citizens-being-unable-to-vote-in-the-european-parliament-elections

Goodwin, M.J. and Heath, O. (2016a). The 2016 referendum, Brexit and the left behind: an aggregate‐level analysis of the result. The Political Quarterly, 87(3), 323-332.

Goodwin, M.J. and Heath, O. (2016b). Brexit vote explained: poverty, low skills, and lack of opportunity. Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Goodwin, M., and Heath, O. (2017). UK 2017 General Election Examined: Income, Poverty and Brexit. Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Mellon, J., Evans, G., Fieldhouse, E., Green, J. and Prosser, C. (2018). Brexit or Corbyn? Campaign and Inter-Election Vote Switching in the 2017 UK General Election. Parliamentary Affairs, 71(4), 719-737.

O’Carroll (2019). ‘Many EU citizens will be unable to vote in UK, campaigners warn.’ The Guardian. 21 May 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2019/may/21/european-elections-many-eu-citizens-will-be-unable-to-vote-in-uk-campaigners-warn

Vaccari, C., Smets, K. and Heath, O. (forthcoming). The United Kingdom 2017 Election: Polarization in a Split Issue Space. West European Politics.

Walker, P. (2019). Tories and Labour suffer Brexit backlash as Lib Dems gain in local elections. The Guardian. 3 May 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2019/may/03/liberal-democrats-conservatives-labour-local-elections-brexit-2019