Introduction

The elections for the European Parliament in Finland took place in the aftermath of the national parliamentary elections that took place on 14 April 2019. In this election, the Social Democratic Party (SDP) with 17.7% of the votes narrowly edged out the right-wing populist Finns party (PS) with 17.5% in second and the conservative National Coalition Party (KOK) in third with 17.0% of the votes.

Consequently, the election campaign for the EP elections was rather short. The debate centred on the possible success of the Eurosceptic PS, since the party was expected to ride on the wave of Eurosceptic parties in EP elections (De Vries, 2018).

The closeness of elections was expected to decrease turnout in the EP elections, which in 2014 was 41.0% (Mattila, 2003). Finland has had one of the lowest turnouts (10%) of young voters (18-24) in 2014, second only to Slovakia (6%), although there were signs that this would increase this time around.

Due to the limited number of candidates, even major changes in vote shares are unlikely to lead to parties winning or losing more than a single seat. However, what candidates win a seat is always uncertain in Finland’s open list proportional system, where voters rather than party elites decide what candidates gain a seat (von Schoultz, 2018). It was therefore unclear what candidates would gain seats for most parties.

Parties and Issues

Having won the national elections, SDP used the slogan “we don’t Brexit, we Fixit” shown in Figure 1 to position itself as the main contender for overseeing the Finnish EU Presidency beginning July 2019.

Figure 1. SDP slogan

Nevertheless, most polls suggested it would come third or even fourth in the EP elections, only getting two seats in the new EP. Candidates included former party leader Eero Heinäluoma, but otherwise there were few prominent candidates.

Together with SDP, KOK and the Centre party (KESK) are traditionally the three main parties in Finnish politics. Both were expected to lose votes, although it was uncertain whether this would translate into a loss of seats. KOK was expected to lose votes but it would remain the largest party. Three current MEPs ran for re-election, but former Prime Minister Alexander Stubb, who was a popular candidate in the 2014 elections, did not run this time. The rural-liberal KESK risked losing one of their three seats if it would repeat the loss suffered in the national elections. Two of the current MEPs were running but were challenged by prominent party cadres.

Two parties challenged their dominance. The right-wing populist Finns Party (PS) was polling to build on their success and become the second largest party in terms of votes, thereby gaining a third seat in the EP. PS:s list included several prominent candidates, including six newly elected MPs on the list. The Green League (VIHR) was also expected to win votes, and some polls suggested it could become the second largest party in terms of votes and win three seats in the process. The candidates included veteran MEP Heidi Hautala and former party leader Ville Niinistö.

The leftist Left Alliance (VAS) was expected to keep their single seat, while the Swedish People’s Party (RKP) struggled to gain a seat in the EP. MEP Merja Kyllönen was running for re-election, but had publicly stated that if elected, she would not take up the position since she preferred to work in the national parliament, where she won a seat. RKP is a minority party that mainly represent the linguistic minority of Swedish-speaking Finns. Polls suggested they were unlikely to win a seat, and even if the party is consistently underrated in polls, RKP needed to rally most Swedish speakers to vote for them to successfully defend their seat in EP. Current MEP Nils Torvalds spearheaded the list that otherwise included several young candidates.

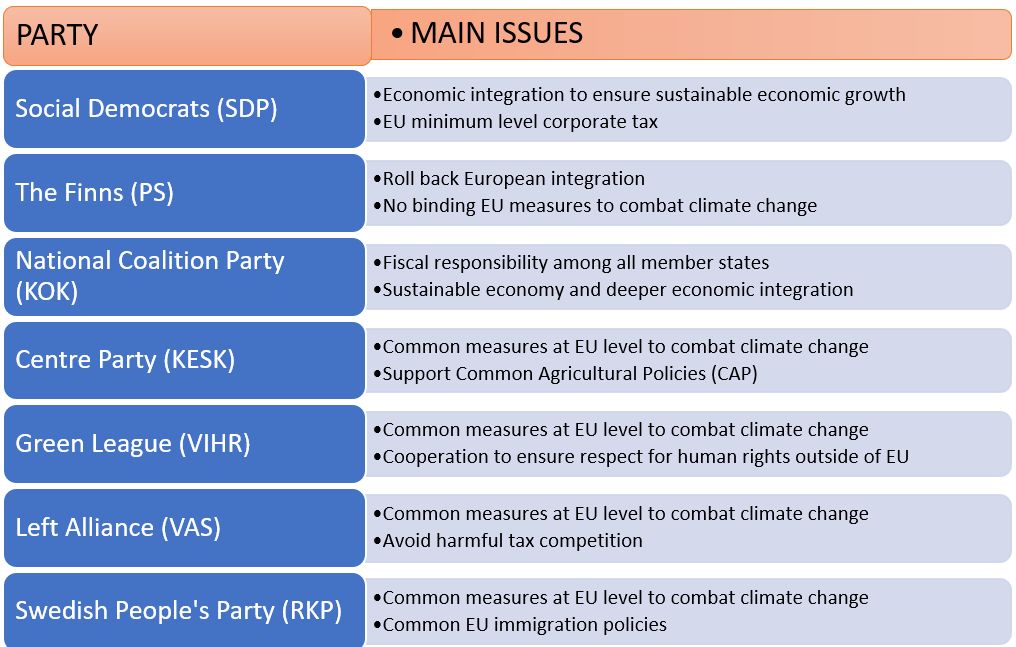

While integration was certainly an issue in the debates, much of the debate focused on genuine EU topics rather than national issues, as is otherwise often the case (Schmitt and Toygür, 2016). Three EU topics were particularly salient: economic growth, climate change and immigration policies. Table 1 shows the position of the parties.

Table 1. Party positions on main issues

The economic debate focused on tax evasion and business competition. SDP, VAS and VIHR argued that corporate tax competition constituted a threat to the welfare state and a minimum community tax would address the problem. The other parties argued that the EU should not take decisions in matter of tax policy.

The role of the EU in combating climate change was also a heated topic during the campaign and here the main cleavage was between the PS and the rest. PS adopted the same strategy as in the national elections by questioning the need for immediate actions, and especially the need for Finland to lead the way in introducing measures. While there were differences in how much it was emphasized, all other parties were in principle positive towards the idea of EU measures to combat climate change.

The debate on immigration revolved mostly on a compulsory quota system for member states. Here most parties (SFP, KOK, VIHR, VAS, RKP) were favourable while KESK maintained that the idea was irrelevant since it would never be acceptable to other member states and PS opposed the idea completely.

The debate between the top candidates for the European Commission Presidency held in Brussels on 15 May gathered some interest in national media. Several major media outlets provided a commentary and it was generally perceived to have been a quiet affair where no major disagreements existed between the candidates.

The results

Advance voting is popular in Finland, and about 21% of all registered voters had voted by May 21, which suggested that the turnout would be about the same as in 2014. In the end, the turnout increased slightly compared to 2014 since 42.7% of all eligible voters cast their vote.

When the results of the advance voting were announced, it seemed like the expectations would largely be fulfilled. As more votes were counted, some developments occurred, but the overall picture remained similar. Three hours after the closing of the polling stations, the preliminary results were available for the whole country. In the end, the outcome confirmed the expectations that KOK would remain the first party with 20.8% of the votes resulting in three seats. However, even more successful were the greens (VIHR), which became the second largest party with 16.0%, a 6.7%-points increase in comparison to 2014, gaining a second seat. SDP also gained votes in comparison to 2014 (+2,3%) and received 14.6% of all votes resulting in two seats, somewhat below their result in the national elections. PS gained 1.0%-point compared to 2014, but the 13.8% result was disappointing considering the 18% forecasted before the elections. KESK was the major loser and only got 13.5% of the votes, 6.1%-points less than in 2014 and losing one seat. VAS got 6.9% of the votes and kept their seat. The most important development during the evening was that RKP increased their share of the votes to 6.3% and climbed the list to cling on to the 13th seat.

The battle for the 14th place “Brexit-seat” was very close and it changed several times what party would win the reserve seat. In the end, it went to the Greens, who would win an additional seat when Brexit is completed and Finland gets another seat in EP.

| Table 2 – Results of the 2019 European Parliament elections – Finland | ||||||||

| Party | EP Group | Votes (N) | Votes (%) | Seats | Seats in case of Brexit | Votes change from 2014 (%) | Seats change from 2014 | Seats change from 2014 in case of Brexit |

| National Coalition Party (KOK) | EPP | 380106 | 20.8 | 3 | 3 | -1.8 | +0 | +0 |

| Green League (VIHR) | G-EFA | 292512 | 16.0 | 2 | 3 | +6.7 | +1 | +2 |

| Social Democratic Party (SDP) | S&D | 267342 | 14.6 | 2 | 2 | +2.3 | +0 | +0 |

| Finns Party (PS) | ECR | 252990 | 13.8 | 2 | 2 | +1.0 | +0 | +0 |

| Centre Party (KESK) | ALDE | 247416 | 13.5 | 2 | 2 | -6.1 | -1 | -1 |

| Left Alliance (VAS) | GUE-NGL | 125749 | 6.9 | 1 | 1 | -2.4 | +0 | +0 |

| Swedish People’s Party (RKP) | ALDE | 116033 | 6.3 | 1 | 1 | -0.4 | +0 | +0 |

| Christian Democrats (KD) | EPP | 89166 | 4.9 | 0 | 0 | -0.4 | +0 | +0 |

| Others | 57485 | 3.1 | ||||||

| Total | 1828799 | 100 | 13 | 14 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Turnout (%) | 42.7 | |||||||

| Legal threshold for obtaining MEPs (%) | none | |||||||

Conclusion

The prognoses were dire both in terms of turnout and results. When seen in this light, the result may be considered a cautious win for the pro-EU side. While a turnout of 42.7% is by no means impressive, it is satisfactory considering the context and the proximity to the national elections.

Furthermore, the projected win for the Eurosceptic forces did not materialize in Finland, where the most successful parties all championed pro-integration agendas for ensuring economic growth and combatting climate change. Although PS gained votes, they failed to win an additional seat and clearly underperformed compared to the forecasts.

The results replicated the results from the national elections in the sense that rather than three big parties and several small, there are now several mid-sized parties in Finnish politics. Otherwise, the EP 2019 elections was one of the rare occasions where most parties found reasons to be satisfied with the outcome. Even KESK, the only party that lost a seat, was content that the loss was not even more pronounced.

The European wave of support for green parties finds resonance in Finland, where the main message from the voters seem to be that they expect the EP to take the lead when it comes to efforts to combat climate change.

References

De Vries, C. E. (2018). Euroscepticism and the Future of European Integration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mattila, M. (2003). Why bother? Determinants of turnout in the European elections. Electoral Studies, 22(3), 449-469.

Schmitt, H. and Toygür, I. (2016). European Parliament Elections of May 2014: Driven by National Politics or EU Policy Making?. Politics and Governance, 4(1), 167-181.

Von Schoultz, Å. (2018). Electoral Systems in Context: Finland. In E. S. Herron, R. J. Pekkanen and M. S. Shugart (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Electoral Systems (601-626). Oxford: Oxford University Press.