The European Parliament elections of 2019 in Greece took place on 26 May together with municipal and regional elections. The governmental party of the radical left SYRIZA suffered severe losses and the centre-right party of New Democracy (ND) increased its electoral strength and dominates again in the Greek party system after the period 2012-2015. The outcome of the election had immediate consequences for the national electoral arena. On the night of the election, the Greek PM Alexis Tsipras called for snap elections (four months ahead) to be held on 7 July 2019.

The context

The 2019 European election in Greece was the first contest after the national elections in September 2015. After a very busy political timeline from 2012 to 2015 with four consecutive national elections, the 2014 EP election and the referendum of 2015 on acceptance or rejection of an EU/IMF lending proposal (the third bailout agreement since 2010), the Greek electorate went to the polls to elect the representatives in the European parliament. The majority of citizens still share high percentages of Eurosceptical attitudes towards the EU (e.g. only 25% have a positive image towards the EU according to the standard Eurobarometer 90 in autumn 2018 while the European average is 43%) – a characteristic which has appeared since the onset of the economic crisis.

From the 2014 European election to the one in 2019, the country experienced a tense period both in economic and socio-political terms. Under the first coalition government between SYRIZA and the nationalist right-wing party of Independent Greeks/ANEL (formed in the aftermath of the January 2015 national elections) the country entered a phase of sharp economic instability. SYRIZA won again the September 2015 snap election and formed another coalition government with ANEL. During this second term, the government had to implement a harsh economic programme creating disillusionment among its supporters. Moreover, the coalition government agreed with the creditors on the third and last bailout programme which expired on 20 August 2018. Overall, during the last year before the European election one could say that the Greek economy had been stabilized. However, social and political dissatisfaction was particular high. Unemployment rates were down but still high (18.5% in February 2019) and more severe taxes have been imposed especially for the middle/upper class. Additionally, there was a sense of a growing “tiredness” of citizens with the perceived ineffective and sometimes dangerously inept administration of SYRIZA (e.g. the fires in the summer of 2018 in the Attica region with 101 deaths). The coalition government formally ended in February 2019 due to the disagreement between the two parties over the Macedonia name dispute. On 12 June 2018, an agreement was reached between Greek PM Alexis Tsipras and his counterpart Zoran Zaev, whereby the name “Republic of North Macedonia” would be adopted. It was an international issue that had remained unsolved for more than 20 years, but according to the majority of Greeks (and especially those living in the Greek region of Macedonia) the agreement was a bad one for Greece and the PM himself was often labelled as a “traitor” by nationalist opposition groups. Therefore, part of the explanation for the losses of SYRIZA can be attributed to this issue, especially in Northern Greece.

The electoral campaign: European elections without Europe

The debate between the two main parties, SYRIZA and ND overshadowed any other aspect of the campaign. National issues – especially the future of the Greek economy and the Macedonia dispute – were predominant. The election was a typical referendum contest with a very high level of polarization. The socialist party of PASOK has tried to mobilize and attract part of its old electorate and posed itself as an alternative political solution. It participated in the centre-left coalition Movement for Change (KINAL) which was founded in March 2018. In these European elections some new parties participated. Among them the “Course of Freedom” by Zoe Kontantopoulou, a former SYRIZA MP, the new pan-European party European Realistic Disobedience Front (DiEM25) formed by Yanis Varoufakis, a former MP of SYRIZA and ex-minister of Economics, as well as Greek Solution by Kyriakos Velopoulos, an ex-parliamentary member of the nationalist Popular Orthodox Rally (LAOS) who had been also a member of ND from 2012 to 2015. Overall, 40 parties participated from the communist left to the extreme right. A proportional electoral system with a 3% electoral threshold and open lists (since 2014) were adopted. The latter feature produced a personalized electoral campaign with EP candidates running individual campaigns throughout Greece. A major issue was the mobilization of younger voters. A significant change compared to previous elections was the passage of a new electoral law by SYRIZA government, in which the eligible age for voting changed from 18 years to 17 years old.

SYRIZA claimed that this election should be seen as a vote of confidence to the government after the end of the bailout programmes. Its main slogans were “We have the power, we do not go back”, “We join our forces. For the Greece of the many, for a Europe of the peoples”, “The time of the many has arrived!”. The party accused ND for supporting the candidacy of Manfred Weber from the European People’s Party as next President of the European Commission. Weber is widely perceived as a champion of austerity for the countries of Southern Europe. On the other hand, ND highlighted the necessity for change: “On 26 May we vote for political change”. Its leader, Kyriakos Mitsotakis promised an economic programme with a restructuring of the taxation system aiming to reduce the taxes, while SYRIZA pushed through welfare and pension benefits, as well as favourable payment plans for taxpayers with arrears, in the run-up to the contest. Almost no political actor talked about European issues. This is particular striking given the fact that in both the economic and ongoing refugee-immigration crises, Greece is very much involved and affected.

Turnout

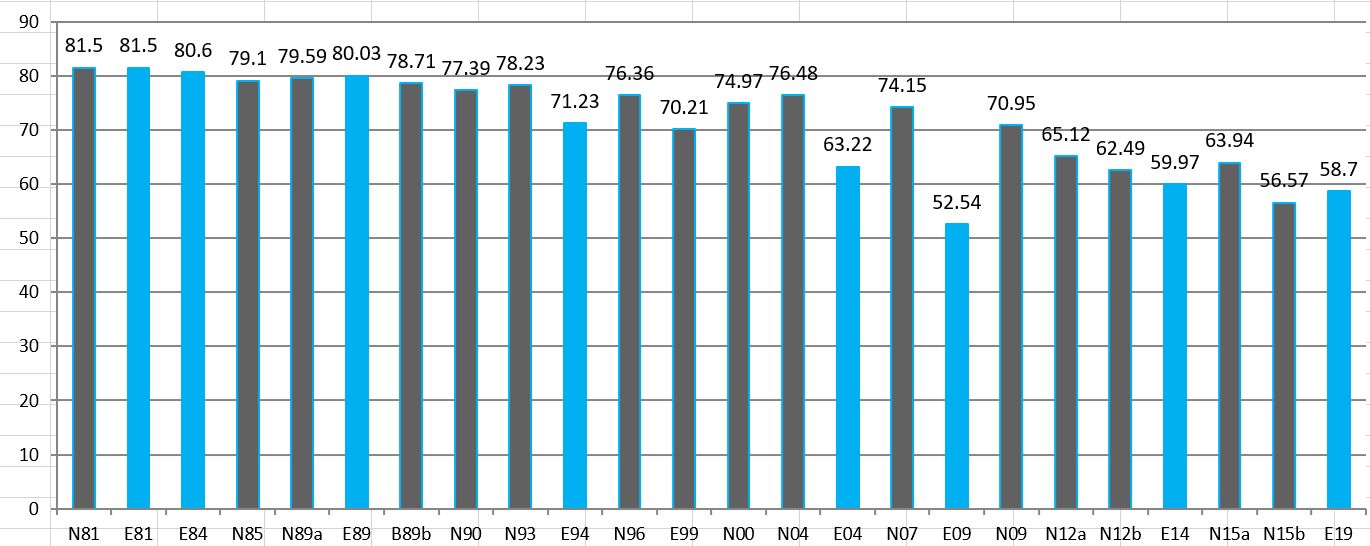

Greece is a country with compulsory voting even though the relevant penalties for not voting are never imposed. Participation reached 58.7%, as shown in Figure 1. It decreased by 1.27% compared to the 2014 European election, but there is an increase compared to the previous national elections of September 2015 (+2.13% or 352,507 more voters). Nevertheless, we have to interpret these differences with caution given the increase of 161,289 registered voters compared to 2015 because of the inclusion of younger voters.

| Figure 1 – Turnout % in National (N) and European (E) elections in Greece 1981-2019 | |

| N81 | 81.5 |

| Ε81 | 81.5 |

| Ε84 | 80.6 |

| N85 | 79.1 |

| N89a | 79.59 |

| E89 | 80.03 |

| B89b | 78.71 |

| N90 | 77.39 |

| N93 | 78.23 |

| Ε94 | 71.23 |

| N96 | 76.36 |

| Ε99 | 70.21 |

| N00 | 74.97 |

| N04 | 76.48 |

| Ε04 | 63.22 |

| N07 | 74.15 |

| Ε09 | 52.54 |

| N09 | 70.95 |

| N12a | 65.12 |

| N12b | 62.49 |

| Ε14 | 59.97 |

| N15a | 63.94 |

| N15b | 56.57 |

| E19 | 58.7 |

Source: own elaboration from data from the Minister of Interior

The results

The election stands as another example of a momentous contest in the history of European elections in the country. Back in 2014, there was a historical shift with SYRIZA winning the elections (Teperoglou et al., 2015). This time there is again a shift, but towards a new equilibrium. SYRIZA was severely punished (23.8% of the vote) and the opposition party of ND obtained 33.1 %. The difference (-9.3%) in the vote share between the two parties is the biggest one ever documented in European elections in Greece. The party of ND managed to increase its vote share compared to the national election of September 2015 (+5.03%) while SYRIZA lost much ground (-11.7%). According to the exit poll data (by Metron Analysis, Alco, Marc and MRB opinion poll companies) SYRIZA managed to hold 58% of its electorate of 2015, while the figure for ND was 85%.

The smaller coalition partner, ANEL captured only 0.8% of the total vote (a decrease of 2.89% compared to 2015). Overall, the punishment of the coalition is a classic example of “voting with the boot” (van der Eijk and Franklin, 1996) against the governmental policies given also the fact that the European election took place in the latter term of the first–order national electoral cycle. The concentration of vote among SYRIZA and ND – a total of 56.88% – (compared to 49.28% in 2014) confirms a shift in the Greek party system towards a more modest form of two-partyism which has gradually been restored in the post-crisis period, with SYRIZA replacing PASOK as the major left-of-centre party.

A worthy point to mention is the decrease of the vote share for the neo-Nazi party of Golden Dawn (-2.11% compared to 2015 and -4.51% compared to 2014 European election). This decline could be explained due to internal conflicts and ongoing legal troubles of the party’s leadership, but also because of vote switching of its voters to ND and “Greek Solution”. The electoral performance of KINAL remained stable, but the coalition managed to become the third largest party due to the decline of Golden Dawn. The performance of the communists remained stable too, while the party of The River did not manage to repeat its electoral success of 2014. The breakthrough of the newly formed nationalist party of “Greek solution” is perhaps a typical example of elections that function as a “midwife assisting in the birth of new parties” (van der Eijk and Franklin, 1996). The party of DiEM25 failed to reach the 3% required to elect an MEP for only a few hundred votes.

| Table 1 – Results of the 2019 European Parliament elections – Greece | ||||||

| Party | EP Group | Votes (N) | Votes (%) | Seats | Votes change from 2014 (%) | Seats change from 2014 |

| New Democray (ND) | EPP | 1,873,080 | 33.12 | 8 | +10.4 | +3 |

| Coalition of Radical Left (SYRIZA) | GUE-NGL | 1,343,816 | 23.76 | 6 | -2.8 | +0 |

| Movement for Change (KINAL) | S&D | 436,739 | 7.72 | 2 | -0.3 | +0 |

| Communist Party of Greece (KKE) | NI | 302,673 | 5.35 | 2 | -0.8 | +0 |

| Popular Association-Golden Dawn (GD) | NI | 275,821 | 4.88 | 2 | -4.5 | -1 |

| Greek Solution-Kyriakos Velopoulos | others | 236,365 | 4.12 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Mera25 | 169,293 | 2.99 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Course of Freedom | 90,856 | 1.61 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| The River | S&D | 85,998 | 1.52 | 0 | -5.1 | -2 |

| Centre Union | 82,075 | 1.45 | 0 | +0.8 | 0 | |

| Greece-the other way Notis Marias | 70,288 | 1.24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Popular Orthodox Rally (LAOS) | 69,528 | 1.23 | 0 | -1.5 | 0 | |

| Independent Greeks (ANEL) | ECR | 45,148 | 0.80 | 0 | -2.66 | -1 |

| Other parties | 838,757 | 10.21 | 0 | |||

| Total | 5,920,437 | 100 | 21 | |||

| Turnout (%) | 58.76 | |||||

| Legal threshold for obtaining MEPs (%) | 3% | |||||

Overall, the election could be classified as a national second-order election (following the seminal study by Reif and Schmitt, 1980) only in terms of the losses of the incumbent parties in this type of election and the referendum character of the election. Turnout was higher compared to the previous national election, while the results were not favourable for smaller parties with the exception of the newly formed nationalist party.

The consequences and conclusions

The 2019 European election – similar to the one of 2014 – could serve as a prelude of a shift in the balance of power in the forthcoming national elections. This time, presumably, the party of ND will win the national elections of 7 July 2019. The first major lesson of this election is that a second-order election prefigures changes on first-order electoral politics, rather than the other way around (Schmitt and Teperoglou, 2018). A second lesson is that the Greek party system has entered a new period of stabilization.

References

Reif, K. and Schmitt, H. (1980). Nine second-order national elections – a conceptual framework for the analysis of European election results. European Journal of Political Research, 8(1), 3–44.

Schmitt, H. and Teperoglou, E. (2018). Voting behaviour in multi-level electoral systems. In J. Fisher, E. Fieldhouse, M. N. Franklin, R. Gibson, M. Cantijoch and C. Wlezien (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Elections, Voting Behaviour and Public Opinion (232-243). Abingdon: Routledge.

Teperoglou, E., Tsatsanis, E. and Nicolacopoulos, E. (2015). Habituating to the New Normal in a Post-earthquake Party System: The 2014 European Election in Greece. South European Society and Politics, 20(3), 333-355.

Van der Eijk, C. and Franklin, M. N. (1996). Choosing Europe? The European Electorate and National Politics in the Face of the Union. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.