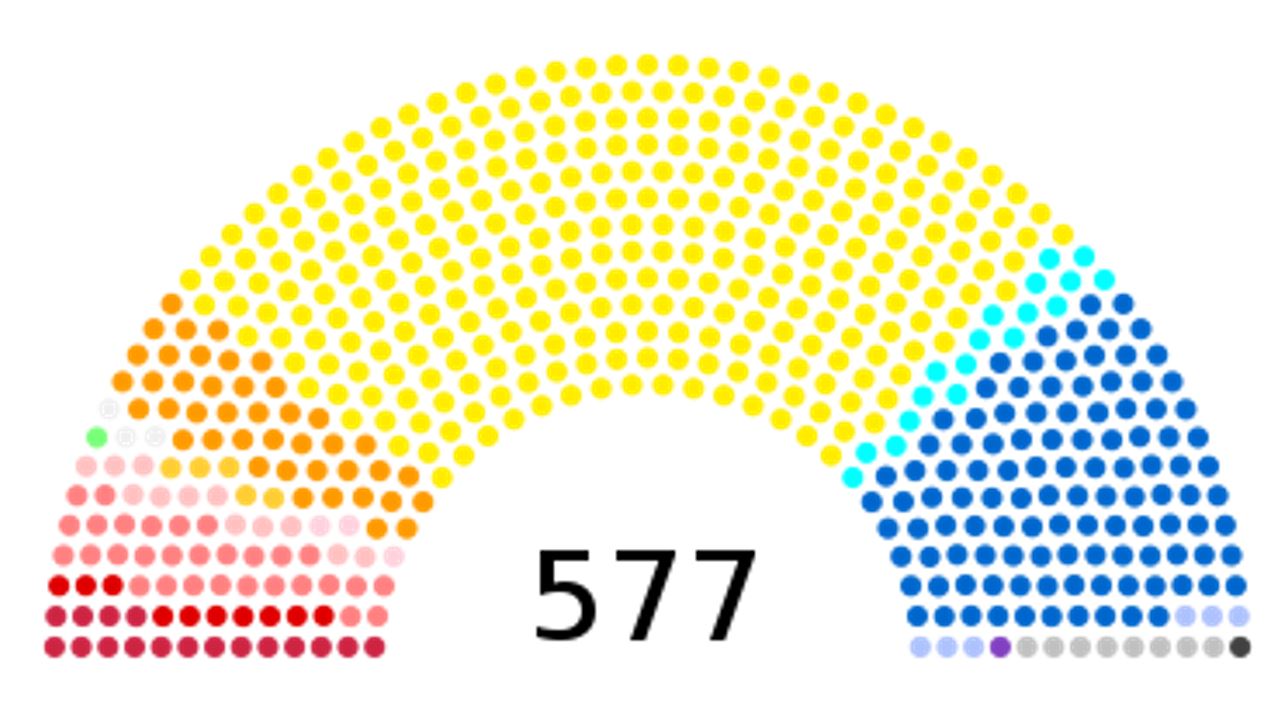

Emmanuel Macron’s presidential majority – consisting of his movement La République En Marche (LREM) and centrist party Modem – has largely win the second round of the legislative elections on June 18, although with a smaller margin than predicted after the first round. LREM on its own has obtained the absolute majority in the lower house with 308 seats out of 577. Mainstream parties of the left and the right realized some of the worst electoral performances in parliamentary elections: the Parti Socialiste (PS) hits a record low, with only 30 MPs, and making a parliamentary group of a little over 40 MPs with its traditional allies. Conservatives (LR) and centre-right obtain 120 members of parliament, although the will seat divided in parliament, as a third of right-wing MPs will support the government whereas the rest stands in the opposition. The radical left, under the lead of Jean-Luc Mélenchon, performs better than expected, with a total of 30 MPs, which have been unable to form a unitary group. The Front National achieves its best score under the two-round majoritarian electoral system, sending 8 representatives to parliament, including party leader Marine Le Pen.

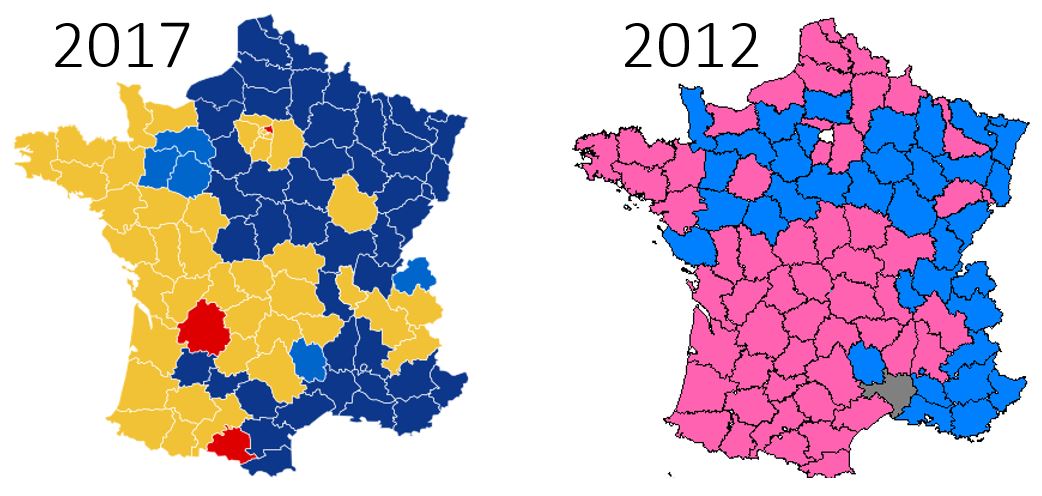

Fig. 1 – Composition of the next National Assembly In addition to this unprecedented composition of parliament with a hegemonic centrist majority, flanked by smaller opposition groups on the left and on the right, the low turnout constitutes the historical result of this election. 57.4% of registered voters did not turn out to the polling station for the second round of the election. This is 8% more non-voters than for the first round, and it sets a new historical record. Traditionally, participation is lower in the legislative elections than in the presidential elections, but the ongoing trend suggests that legislative elections have become “second order elections”. Indeed, because they occur 6 weeks after, the legislative elections have become subordinated to the presidential election, which is the most salient. This trend has been steadily increasing since 2002, the first election with a “reversed calendar”, in which legislative serve as a “confirmation election” or a “third round” after the election of the president. The stake of the legislative election is now reduced to “giving a majority” to the freshly elected president. In such cases, the president’s party usually manages to obtain the support of a majority of its voters, while opposition parties are faced with largely demobilized voters. In the legislative elections, the most vocal opponents of Macron, la France Insoumise (LFI, radical left) and the Front National (FN) have only obtained between half and third of the votes they received in the presidential election.

In addition to this unprecedented composition of parliament with a hegemonic centrist majority, flanked by smaller opposition groups on the left and on the right, the low turnout constitutes the historical result of this election. 57.4% of registered voters did not turn out to the polling station for the second round of the election. This is 8% more non-voters than for the first round, and it sets a new historical record. Traditionally, participation is lower in the legislative elections than in the presidential elections, but the ongoing trend suggests that legislative elections have become “second order elections”. Indeed, because they occur 6 weeks after, the legislative elections have become subordinated to the presidential election, which is the most salient. This trend has been steadily increasing since 2002, the first election with a “reversed calendar”, in which legislative serve as a “confirmation election” or a “third round” after the election of the president. The stake of the legislative election is now reduced to “giving a majority” to the freshly elected president. In such cases, the president’s party usually manages to obtain the support of a majority of its voters, while opposition parties are faced with largely demobilized voters. In the legislative elections, the most vocal opponents of Macron, la France Insoumise (LFI, radical left) and the Front National (FN) have only obtained between half and third of the votes they received in the presidential election.

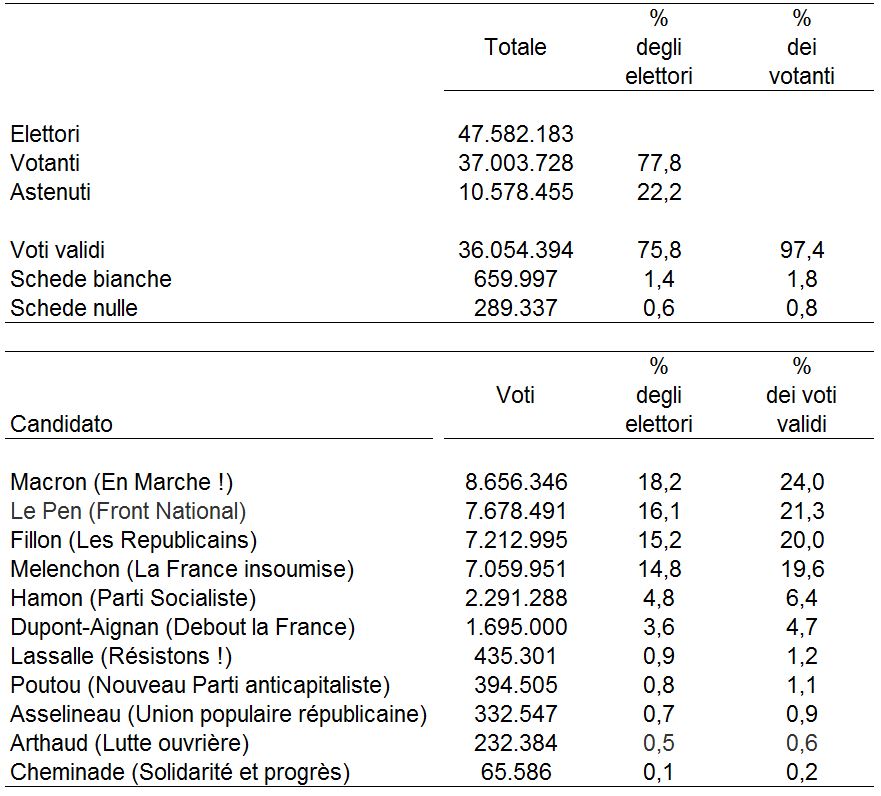

Tab. 1 – Overall electoral results in 2017 French legislative elections

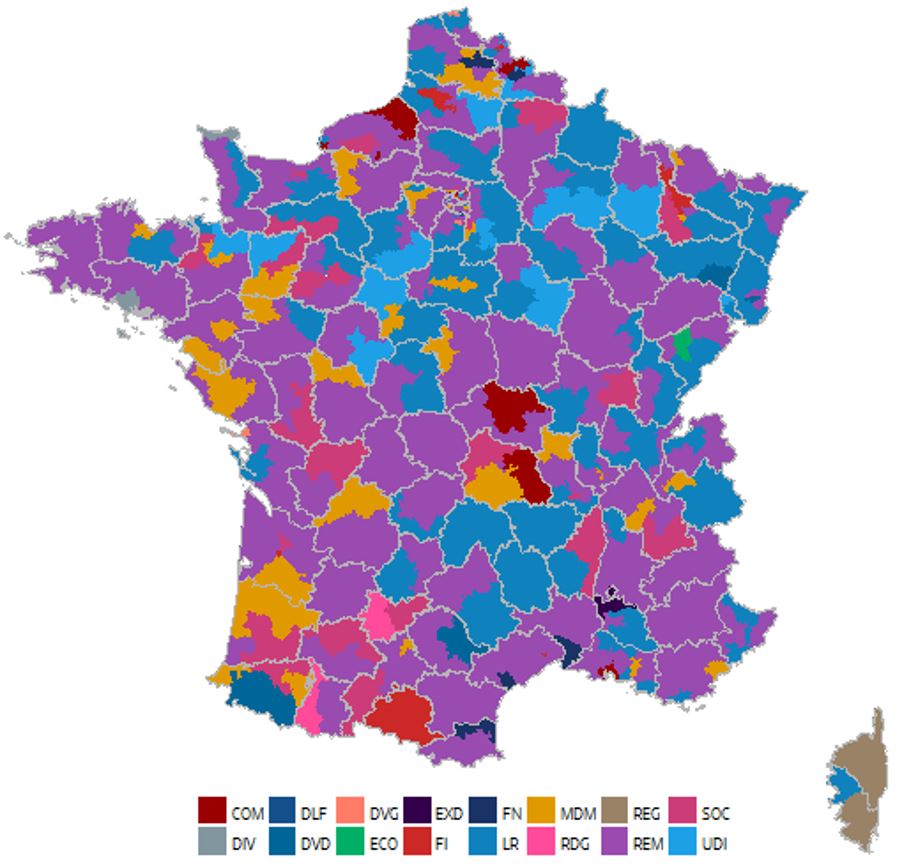

Particularly, each party’s electoral gains is geographically polarized. The radical left has obtained its biggest gain in the former socialist “banlieues” of Paris, while the mainstream right resisted in its traditional strongholds in the East of the country. 5 out of the 8 Front National MPs are elected in the former coal mining districts of the North. LREM, as a new party, has gained MPs all over the country, but clearly establishes its electoral stronghold in the Western part of the country, and particularly in the Bretagne region, which elected 24 LREM MPs out of 27.

Fig. 2 – Map of the district winner in 2017 French legislative elections

LREM’s majority in parliament gives Emmanuel Macron and its government a comfortable margin to lead the economic reforms promised during the campaign. But this political lead is certainly undermined by the high abstention, which appears to be both structural and political. In addition to the usual 15-20% of non-voters, 2017 seems to have been marked by a political abstention, a form of protest through non-voting. The call of some leaders of the left not to choose between Macron and Le Pen in the second round of the presidential election seems to have had consequences in the legislative elections. In addition to record abstention, blank or null votes also skyrocketed. In the second round of the legislative elections, 1,3 million voters cast a blank vote (about 7% of the votes). (newportworldresorts.com) Strikingly, the blank votes increased by a million between the two-round, clearly showing that many voters intended to protest against the political offer of the second round. Overall, the LREM’s majority is large, and stable, but it will always face a legitimacy concern, because the combination of low turnout in a majoritarian system make it one of the most badly elected majority in Europe. Further, these results ask question about the equilibrium of the institutions, and the role of legislative elections. It is a democratic issue when the elections that determine the political majority in parliament are devaluated to this point.