Traduzione a cura di Elisabetta Mannoni

Perché la Spagna ha votato nel 2019?

Questa è la terza volta dal 2015 che gli spagnoli si trovano a votare alle elezioni politiche. La prima volta, i livelli di volatilità elettorale erano stati senza precedenti (oltre il 35% degli elettori aveva cambiato partito tra il 2011 e il 2015) e il numero effettivo di partiti era aumentato in modo significativo, da 3,3 a 5 (Rama Caamaño 2016). Il sistema partitico verteva in una situazione di severa instabilità.

Tra l’altro, nel 2015 l’alto grado di frammentazione parlamentare aveva reso impossibile ottenere il sostegno dalla maggioranza dei deputati per costituire un governo (Simon 2016), così gli spagnoli si erano trovati a dover tornare alle urne per la seconda volta già sei mesi dopo. Il risultato era stato chiaro: il sostegno al conservatore PP (Partido Popular) era aumentato e, sebbene con grosse difficoltà, questo era stato in grado di formare un governo grazie al sostegno esterno di Ciudadanos (Cs).

Tuttavia, meno di due anni dopo, lo scorso giugno 2018, il Partito Socialista (PSOE) ha radunato i partiti all’opposizione per abbattere il governo con un voto di sfiducia, a seguito di una sentenza che condannava il PP per aver beneficiato di finanziamenti al partito ottenuti illegalmente.

Per estromettere il PP, si sono dovute unire le forze di un gran numero di partiti: il PSOE, UP (Unidos Podemos, un partito spesso definito populista), e diversi partiti nazionalisti baschi e catalani. Il voto di sfiducia ha avuto successo ed ha riportato il PSOE al governo. Ciononostante, e sebbene il PSOE contasse del sostegno di UP, il non elevato numero di seggi di entrambi i partiti rendeva necessario trovare un punto d’incontro anche con i regionalisti nel processo di approvazione delle leggi. Quando, a febbraio, i partiti regionalisti catalani si sono rifiutati di sostenere il disegno di legge di bilancio del governo (complice anche la questione del referendum di indipendenza in Catalogna), il primo ministro del PSOE Pedro Sánchez ha chiesto nuove elezioni. Il suo governo è dunque stato piuttosto breve.

Nel 2019, la novità assoluta era il partito nazionalista e nativista spagnolo, Vox, nato da una scissione dal PP nel 2013. Questo partito aveva già ottenuto un sostegno senza precedenti nelle elezioni regionali andaluse del dicembre 2018 (Vittori 2018), e tutti i sondaggi per le elezioni politiche prevedevano che avrebbe raggiunto dai 25 ai 50 (su 350) seggi disponibili in Parlamento (Junquera 2019). Si tratta di un partito che supporta i valori conservatori e il centralismo, e manifesta un forte sentimento di nazionalismo spagnolo, in contrasto con le identità regionali e, in particolare, col secessionismo catalano. Pertanto, le elezioni del 2019 hanno molto in comune con le elezioni del 2016 e, soprattutto, con quelle del 2015. I sondaggi avevano costantemente sottolineato come almeno cinque partiti sarebbero entrati alla Camera (Congreso de los Diputados) con un numero significativo di seggi: PSOE, PP, Ciudadanos, UP e Vox.

I risultati finali confermano parzialmente le previsioni dei sondaggi. In seguito all’emergere nel 2015 di UP – che ha gareggiato con il PSOE a sinistra (Santana and Rama Caamaño 2018), e Ciudadanos – che ha guadagnato spazio nel centro; Vox, l’ultimo partito di medie dimensioni -in competizione con il PP a destra e forse anche in gara per accaparrarsi i voti di chi è più critico nei confronti del sistema (Rama Caamaño and Santana 2019), è entrato in Parlamento con l’10,3% dei voti e 24 seggi. La domanda è chiara: chi compone il bacino elettorale di Vox nel 2019?

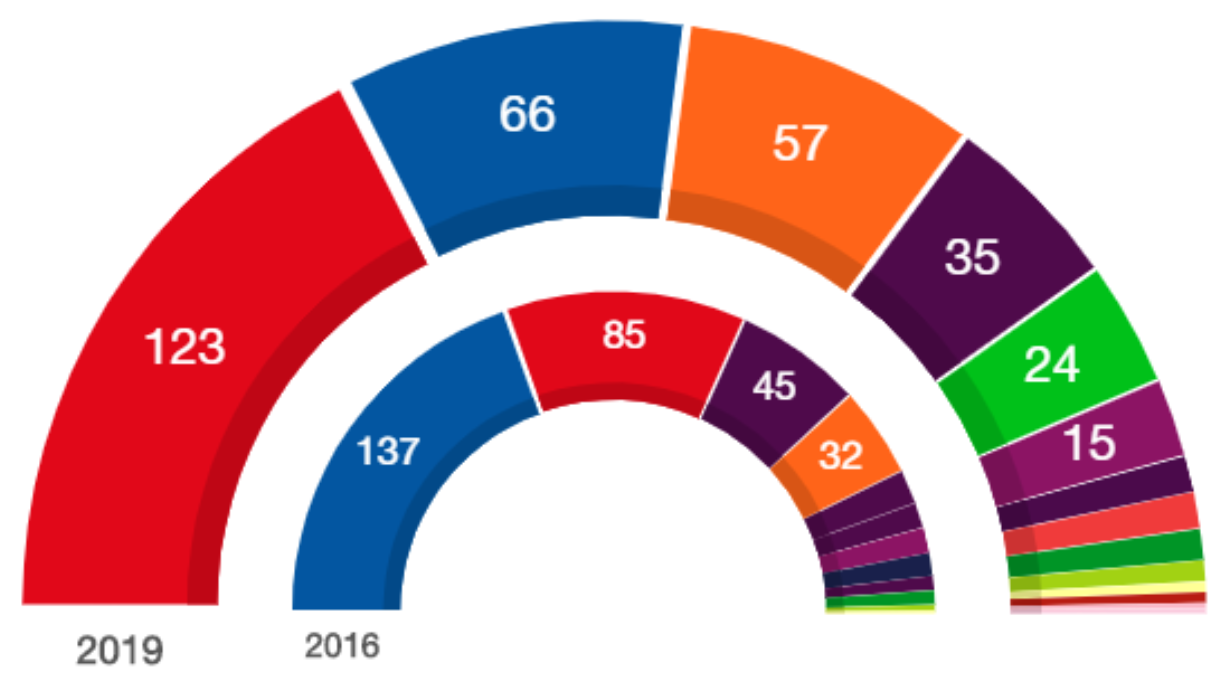

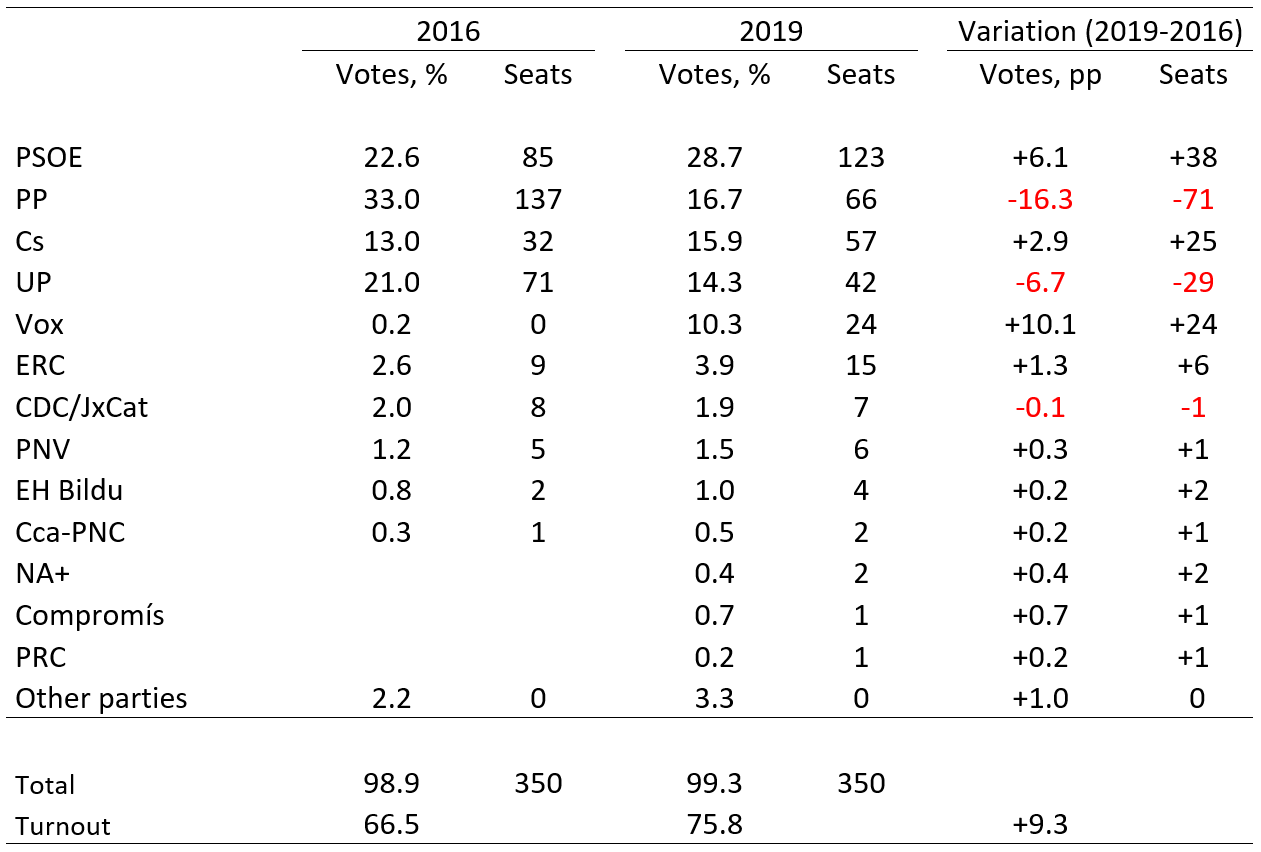

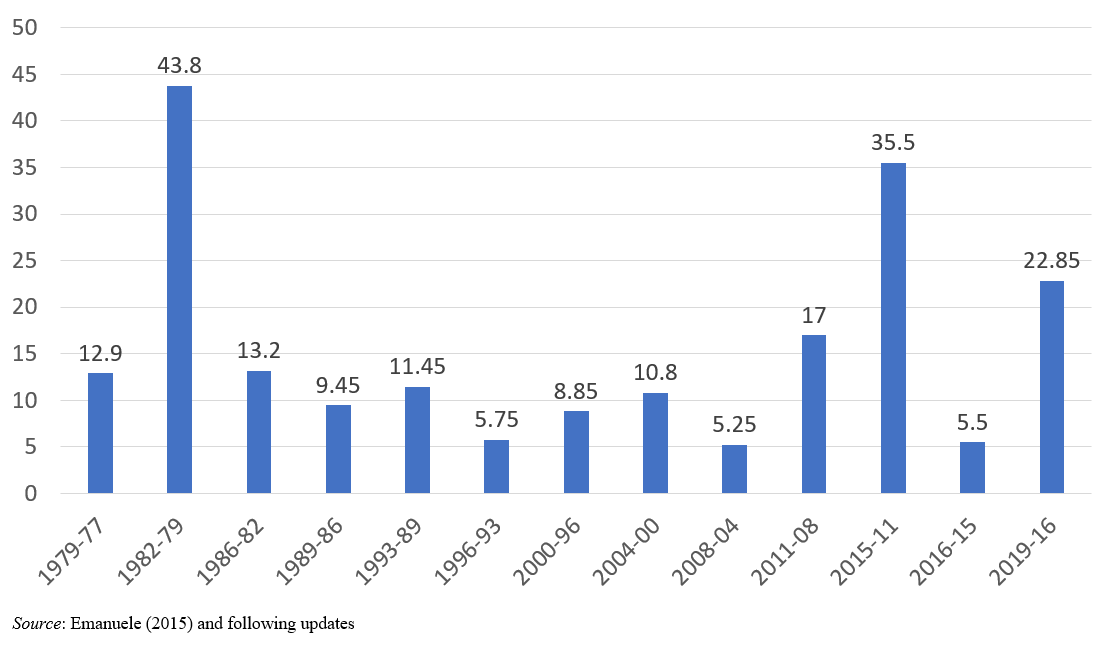

Tab. 1 – Risultati elettorali delle elezioni politiche spagnole nel 2016 e 2019

Lo spettro della volatilità

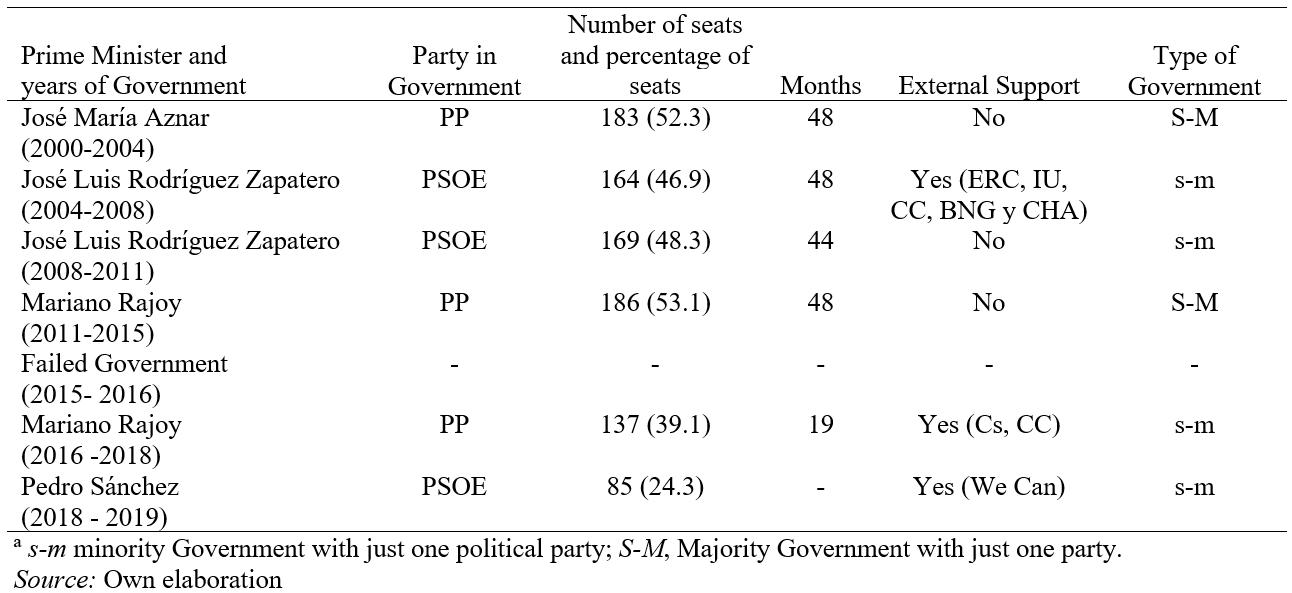

Utilizzando i dati forniti dall’Issue Competition Comparative Project (ICCP), le informazioni che presentiamo sono relative ai cambiamenti tra le scelte di voto delle elezioni del 2016 e l’intenzione di voto nel 2019. Per quanto riguarda Vox, la Tabella 2 mostra che quasi il 19% degli elettori del PP del 2016 e il 17% di quelli di Ciudadanos hanno dichiarato nel 2019 di voler votare per Vox. Sebbene Vox possa essere classificato come partito populista (spesso non è chiara la loro posizione nello spettro ideologico), appare chiaro come il suo elettorato provenga da partiti di destra (Santana and Rama Caamaño 2019).

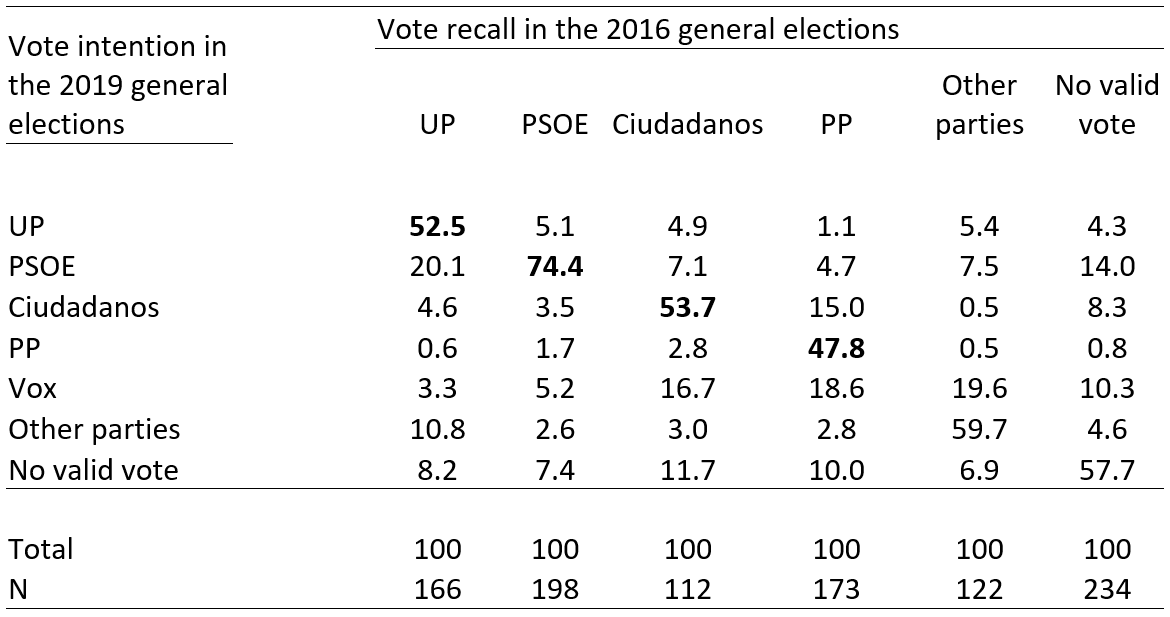

Tab. 2 – Flussi elettorali fra le elezioni politiche spagnole del 2019 e del 2019, destinazioni

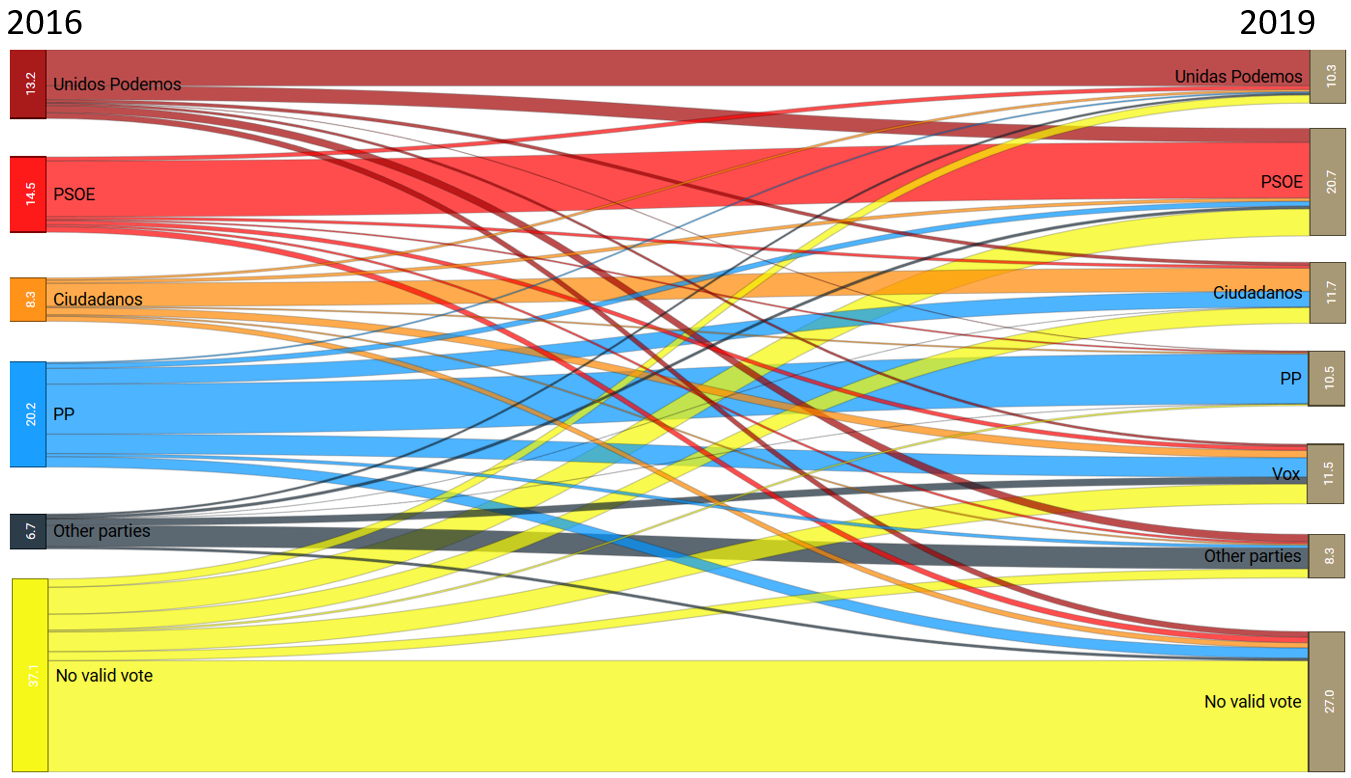

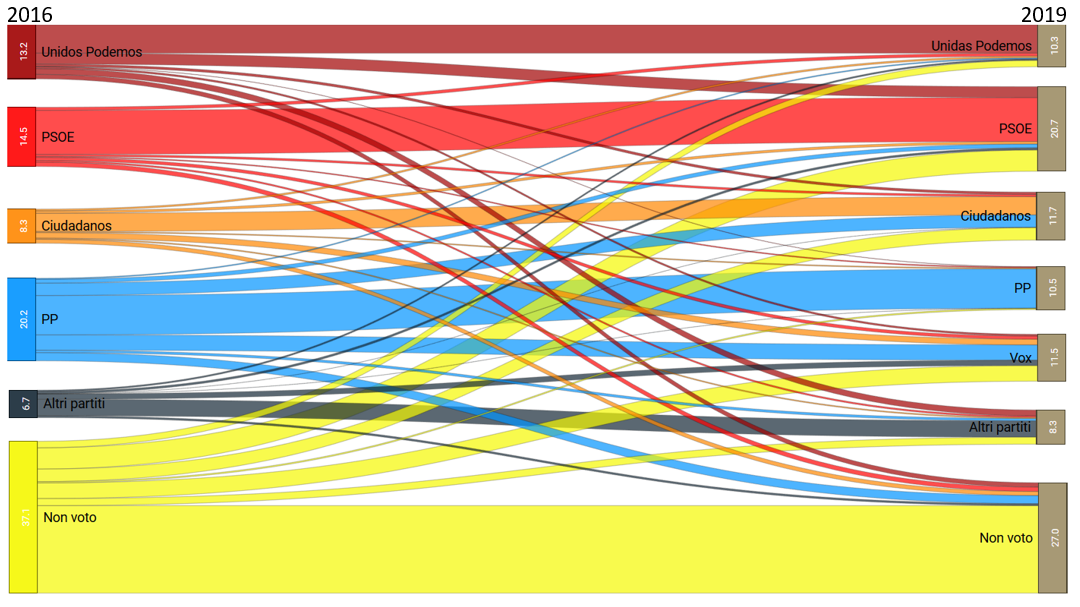

Per essere più espliciti, la Figura 1 mostra i flussi di elettori tra i vari partiti. Anche gli spostamenti tra Podemos e PSOE sono degni di nota. Probabilmente ex elettori di UP in queste elezioni del 2019 hanno votato strategicamente – e questo coordinamento elettorale degli elettori di sinistra è stato cruciale per consentire al PSOE di raggiungere 123 seggi (UP ha perso 29 seggi dal 2016 al 2019 mentre il PSOE ne ha guadagnati 37).

Fig. 1 – Flussi elettorali tra le elezioni politiche spagnole del 2016 e del 2019, percentuali sull’intero elettorato

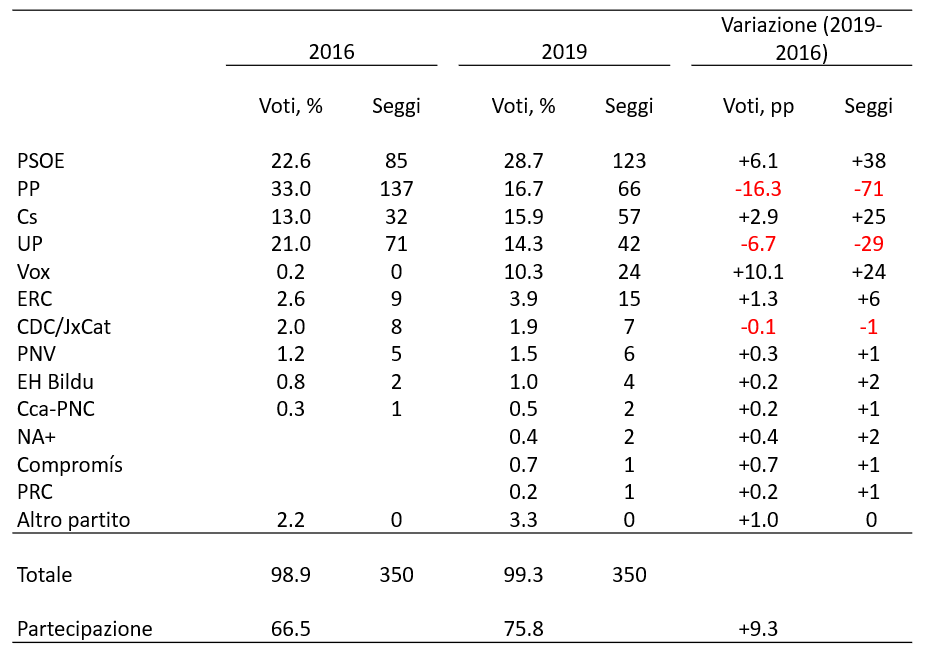

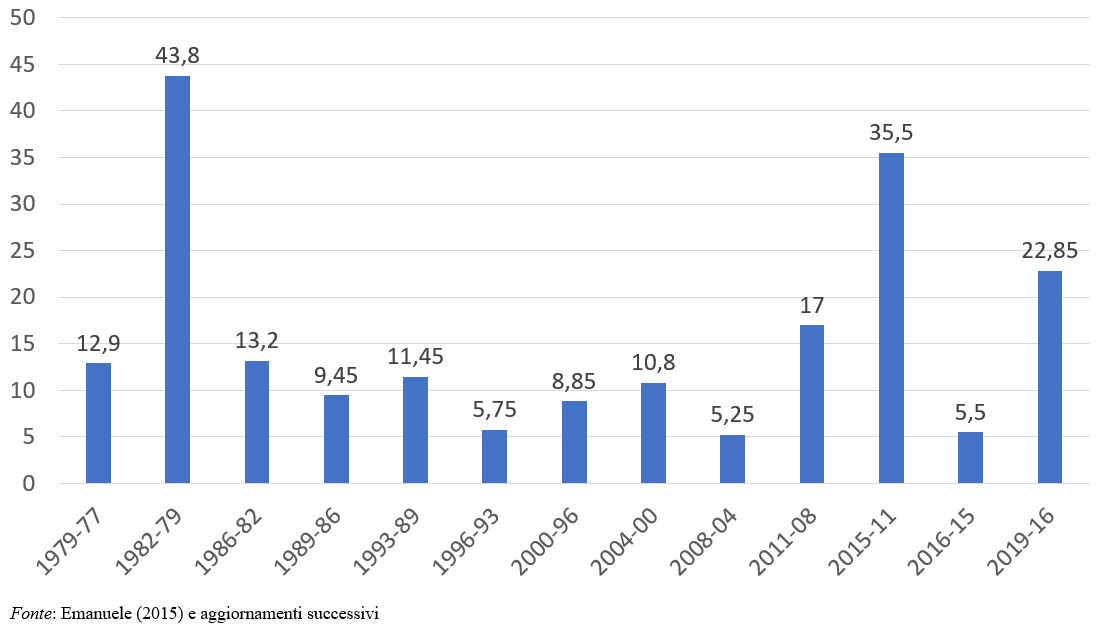

La Figura 2 mostra i livelli aggregati di volatilità elettorale dal 1977 fino al 2019. Le elezioni generali del 2019 si classificano terze nella recente storia democratica spagnola, dopo i livelli record di volatilità raggiunti nelle elezioni del 1982 e del 2015.

Fig. 2 – Livelli di volatilità elettorale nelle elezioni politiche spagnole, 1977 – 2019

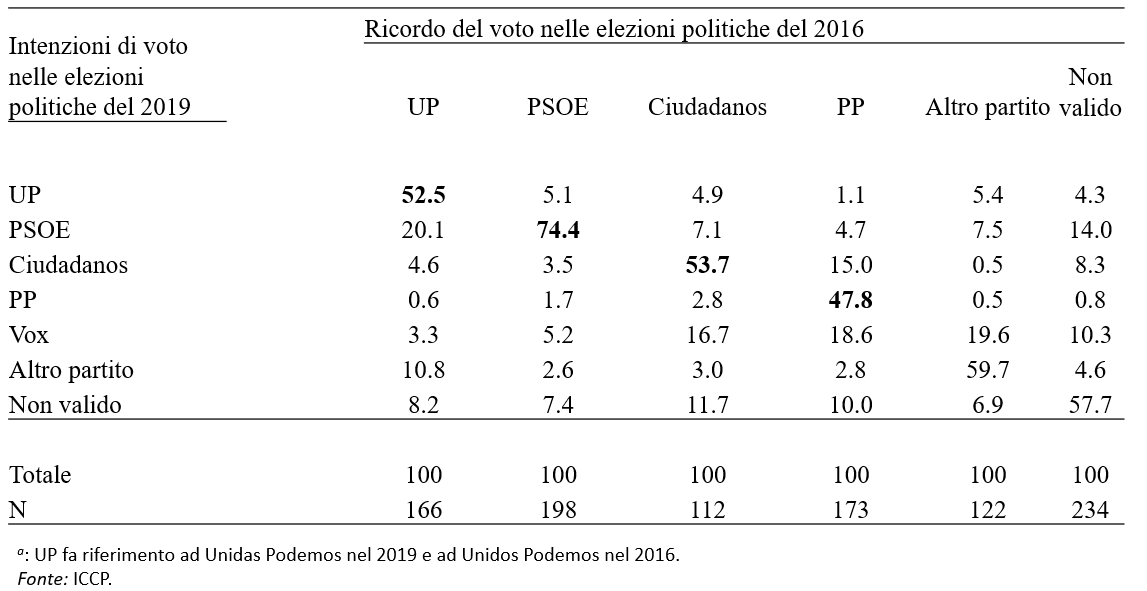

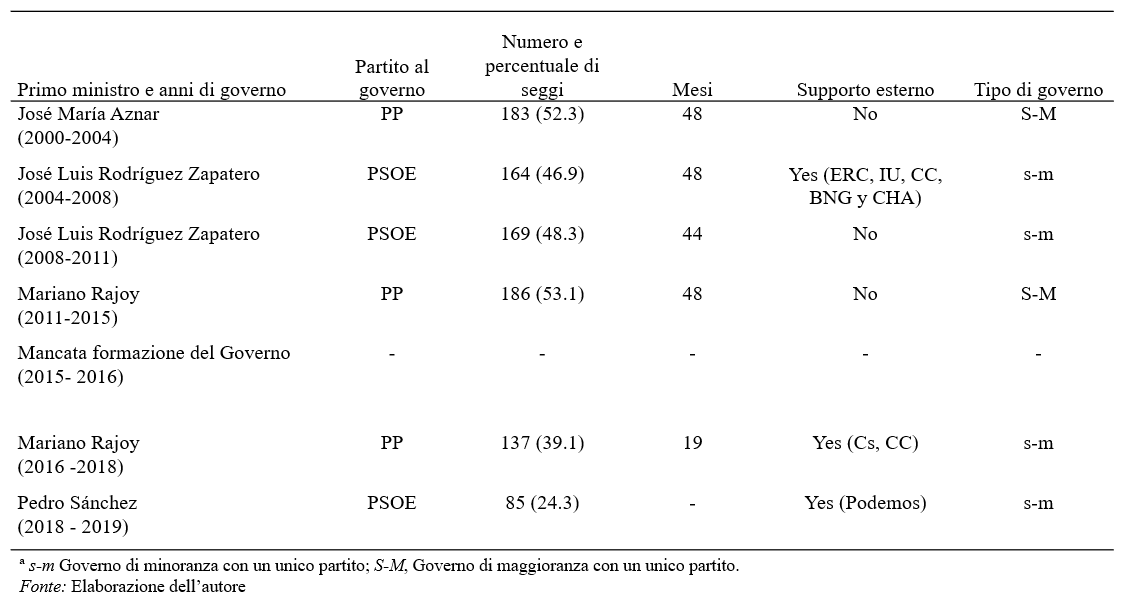

Rispetto a questi livelli di volatilità e frammentazione elettorale, sembra chiaro che – anche stavolta – l’impresa di formazione del governo sarà ardua. La Tabella 3 mostra la formazione dei governi in Spagna dal 1977 fino al 2016.

Tab. 3 – Formazione dei governi in Spagna, 2000-2019 Sebbene il PSOE esca come vincitore da queste elezioni e il PP come principale sconfitto (ha perso più di 70 dei 137 seggi che aveva ottenuto nel 2016), il sottoprodotto evidente di questi risultati elettorali è l’enorme difficoltà che si incontrerà nel tentativo di costruire una coalizione in grado di governare. Quindi, la conseguenza immediata di questa mappa notevolmente più frammentata è un maggior grado di ingovernabilità e di imprevedibilità del sistema politico. L’atomizzazione della rappresentanza politica può portare a legislature più complesse, coalizioni instabili e governi deboli di breve durata.

Sebbene il PSOE esca come vincitore da queste elezioni e il PP come principale sconfitto (ha perso più di 70 dei 137 seggi che aveva ottenuto nel 2016), il sottoprodotto evidente di questi risultati elettorali è l’enorme difficoltà che si incontrerà nel tentativo di costruire una coalizione in grado di governare. Quindi, la conseguenza immediata di questa mappa notevolmente più frammentata è un maggior grado di ingovernabilità e di imprevedibilità del sistema politico. L’atomizzazione della rappresentanza politica può portare a legislature più complesse, coalizioni instabili e governi deboli di breve durata.

Così, sebbene durante la campagna elettorale Albert Rivera, leader di Ciudadanos, abbia ripetutamente dichiarato che non avrebbe partecipato a un governo di coalizione con il PSOE (20 minutos 2019), l’unica semplice coalizione in grado di raggiungere 176 seggi (il Parlamento ne ha 350 totali) è proprio PSOE + Ciudadanos. Altre coalizioni richiederebbero la partecipazione di più di due partiti o, almeno, del sostegno esterno di formazioni politiche minori (regionaliste).

I risultati sono nitidi, ma il futuro, quantomeno in termini di governabilità, in questa domenica di aprile, resta ancora piuttosto sfocato.

Riferimenti bibliografici

Emanuele, V. (2015), Dataset of Electoral Volatility and its internal components in Western Europe (1945-2015), Rome: Italian Center for Electoral Studies

Junquera, N. (2019), ‘New poll predicts Socialist Party victory at Spanish elections’, El País.

Rama Caamaño, J. (2016), ‘Ciclos electorales y sistema de partidos en España, 1977-2016′, Revista Jurídica, 34, pp. 241-266.

Rama Caamaño, J., e Santana, A. (2019), ‘In the name of the people: left populists versus right populists’, European Politics and Society, Online first.

Santana, A., eRama Caamaño, J. (2018), ‘Electoral support for left wing populist parties in Europe: addressing the globalization cleavage’, European Politics and Society, 19(5), pp. 558-576.

Santana, A., e Rama Caamaño, J. (2019), ‘Los votantes de Vox y de Podemos, los más interesados de lejos’, Agenda politica – El País.

Simón, P. (2016), ‘The Challenges of the New Spanish Multipartism: Government Formation Failure and the 2016 General Election’, South European Society and Politics, 21(4), pp. 493-517.

Vittori, D. (2018), ‘Crollo del PSOE nelle regionali in Andalusia: verso il primo governo di centrodestra?’, Centro Italiano Studi Elettorali, disponibile presso: https://cise.luiss.it/cise/2018/12/03/crollo-del-psoe-nelle-regionali-in-andalusia-verso-il-primo-governo-di-centrodestra/