The decision by Theresa May to call a snap election has gone against her. Despite remaining the largest party in Westminster, the Conservatives have fallen short of an absolute majority of seats, and a hung Parliament is the outcome of this election. Jeremy Corbyn has brought the Labour Party to 40% of the votes, the largest result since 2001. In a context characterised by the highest turnout since 1997 (69%), a massive shift back towards a two-party system has occurred: the UKIP has collapsed, the SNP has stepped back, and the Liberal Democrats have not bounced back after the catastrophic 2010 results. While Theresa May’s position seems unstable, she should be leading a new minority government with the support of the Northern Irish Democratic Unionist Party.

The decision by the British Prime Minister, Theresa May, to call a snap election to reinforce her parliamentary majority in view of the Brexit negotiations has been a boomerang: not only hasn’t she strengthened her parliamentary majority, but the Conservatives have also lost the absolute majority of seats in the House of Commons. Table 1 reports the results, in terms of votes and seats, of this 2017 British general election compared to those of the 2015 general election. Despite a notable increase in its share of votes (the best result since Margaret Thatcher’s years), the Conservative party has lost 12 seats, dropping to 317 MPs[1].

Table 1. Results of the 2017 UK general election and comparison with 2015

The Labour party has obtained a remarkable and quite unexpected result, by increasing its share of votes (from the 30.5% to the 40%) and its parliamentary seats (from 232 to 261 MPs). For Jeremy Corbyn, who at the beginning of the campaign was considered nothing more of a weak and unviable leader, this election has a resounding success, since it has brought the Labour Party to the best result in terms of share of votes since 2001 and in terms of seats since 2005.

t is notable from the increase in the share of votes for the two main parties that the format of the party system has substantially come back to a two-party system. Indeed, the aggregate share of votes of Conservatives and Labour is 82.4%, the highest result since 1970. Since then on, the increasing competitiveness of the Liberal Party – and then of the Liberal Democrats – and, more recently, of the UKIP and the Scottish National Party (SNP) contributed to rise party system fragmentation, thus progressively departing from the two-party model which dominated British politics since the mid-1940s onwards.

This outcome has been made possible mainly by the collapse of the UKIP, which emerged as the third largest party in 2015 advocating the exit of the UK from the European Union, and has fallen to 1.8% in this last British general election. Interestingly, UKIP losses have been probably caused by the Brexit referendum, meaning that, after having reached this objective, the party has somewhat lost its main political goal. Yet, it could have been expected that the biggest gainer from the UKIP demise would have been the Conservatives, also given the Hard Brexit stances carried on by many of its prominent politicians. Conversely, and still waiting to obtaining a more fine-grained picture thanks to the analysis of electoral shifts, it is also the Labour Party that seems to have benefitted from the UKIP decline, possibly also thanks to Corbyn’s leftist positions that could have allowed the Labour to attract working-class voters who supported the UKIP in the recent past.

While after the 2015 general election many pundits were commenting about the irresistible rise of the SNP as a new force in the British political landscape, this election has partly debunked this narration: despite maintaining the first rank both in terms of seats and in terms of votes above the Hadrian’s wall, the party led by Nicola Sturgeon has lost 21 MPs. Moreover, after the 2015 catastrophe, the Liberal Democrats have managed to slightly increase their representation in the House of Commons, despite a further decrease in terms of votes, possibly also thanks to a stronger concentration of their votes in some crucial constituencies, especially in Scotland. Also, the Green Party has been severally damaged by the increased concentration of votes into the hands of the two main parties, and has only managed to hold the seat of its leader at Brighton Pavilion. Finally, and this is a crucial piece of information for this story, the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) has gained 10 seats in the House of Commons, its largest result ever. These seats are likely to become a fundamental support for the Conservative government in Westminster.

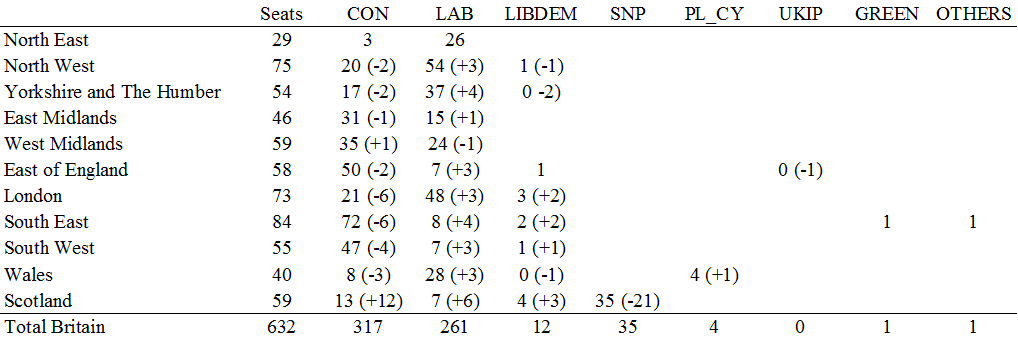

Table 2. Seats by region in Great Britain and differences with 2015

Table 2 reports the seats obtained by parties in Great Britain (Northern Ireland is excluded) disaggregated by region and the difference with respect to 2015. The first striking piece of evidence is the conservative breakthrough in Scotland, where the party moves from 1 to 13 seats, at the expenses of the SNP, thus becoming the second largest party in the region, outperforming the Labour. More generally, Theresa May’s party has lost seats in the rest of the country, especially in London (-6 seats) and in the southern part of the island (-10). Conversely, the Labour Party reinforces its Scottish representation (+ 6 seats), but it has generally gained positions throughout the entire Great Britain.

Overall, the number of seats changing hands is 65[2], exactly the 10% of the seats in the House of Commons, and a third of these changes have occurred in Scotland, the most volatile region from this viewpoint. Indeed, the SNP has lost 12 seats in favour of the Conservatives, 6 to the Labour, and 3 to the Liberal Democrats. From a more general viewpoint, the Labour Party has obtained a net gain of 21 seats against the Conservatives, winning 27 seats where the incumbent was a Tory and losing 6 seats where they were the party of the incumbent MP.

As the reader may recall, some days ago we wrote an article based on the YouGov’s estimates for all the Great Britain’s seats (Northern Ireland was excluded). Some of those seats – 97 – were categorised as lean and tossup ones (where a clear winner was not evident in the polls). What has been the result of the races in such seats? Out of 65 marginal seats with an expected close race between the Conservative Party and the Labour Party, Corbyn’s party has performed slightly better, securing 34 seats against the 31 ones won by the Conservatives. As highlighted before, the Conservative Party has instead gained ground in Scotland by winning 11 out of 12 marginal seats, at the expenses of the SNP. Moreover, the Liberal Democrats have performed pretty well in the marginal challenges against the Conservatives: they have won 7 races out of 11.

What are the prospects for British politics after this general election? The gambling by Theresa May has clearly failed. According to the last news, she should be leading a minority government backed by the right-wing Northern Irish Democratic Unionist Party. It is unclear whether this solution would allow her to stay at 10 Downing Street for the upcoming legislature. For the first time since 1974, and despite the presence of the First-Past-the-Post electoral system, the UK will cope with instability, allegedly resembling what has happened or might happen in many Mediterranean countries. Therefore, despite the Brexit, the United Kingdom is closer to its Southern European counterparts than ever, at least from the political uncertainty viewpoint.

[1] The seat of Kensington (in the London area) has not been assigned yet while publishing this article.

[2] Apart from the missing data from Kensington (see fn. 1), we also do not consider as a switching seat the result of the 2016 by-election in Richmond Park.