Beyond the study of the issues that are considered as a priority, another interesting aspect of the survey conducted by the CISE (Italian Center for Electoral Studies) in view of the next UK general election, refers to the support accorded by voters to 18 positional issues, selected in cooperation with a team of British researchers. Specifically, each respondent was asked to position himself on a 6-point scale where the points 1 and 6 represent the two rival goals to be pursued on a given issue[1]. Looking at the configuration of voters’ support for the different issues will allow us to reach a clear understanding about what voters want and, consequently, about the structure of opportunity available for parties in this electoral campaign. Moreover, this analysis will also pursue another aim: investigating whether the support for the different goals can be aggregated to form one (or more) consistent dimension(s) of competition or, conversely, whether such support has an idiosyncratic shape. In other words, is the mind of voters ideologically consistent or not? Do voters still rely on the traditional left-right dimension of competition or do they simply support different positions on different goals without any reference to the 20th-century-style alignments?

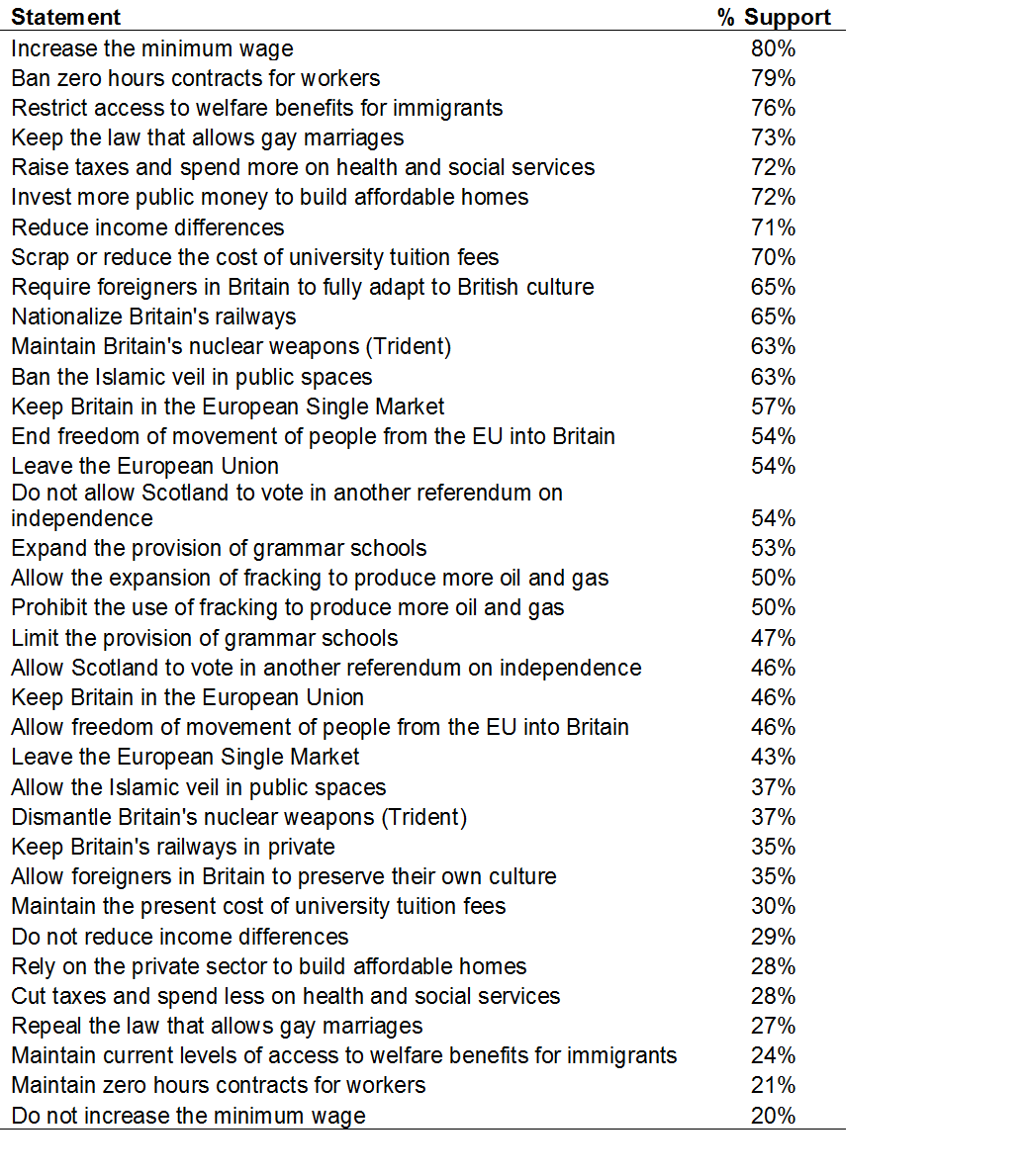

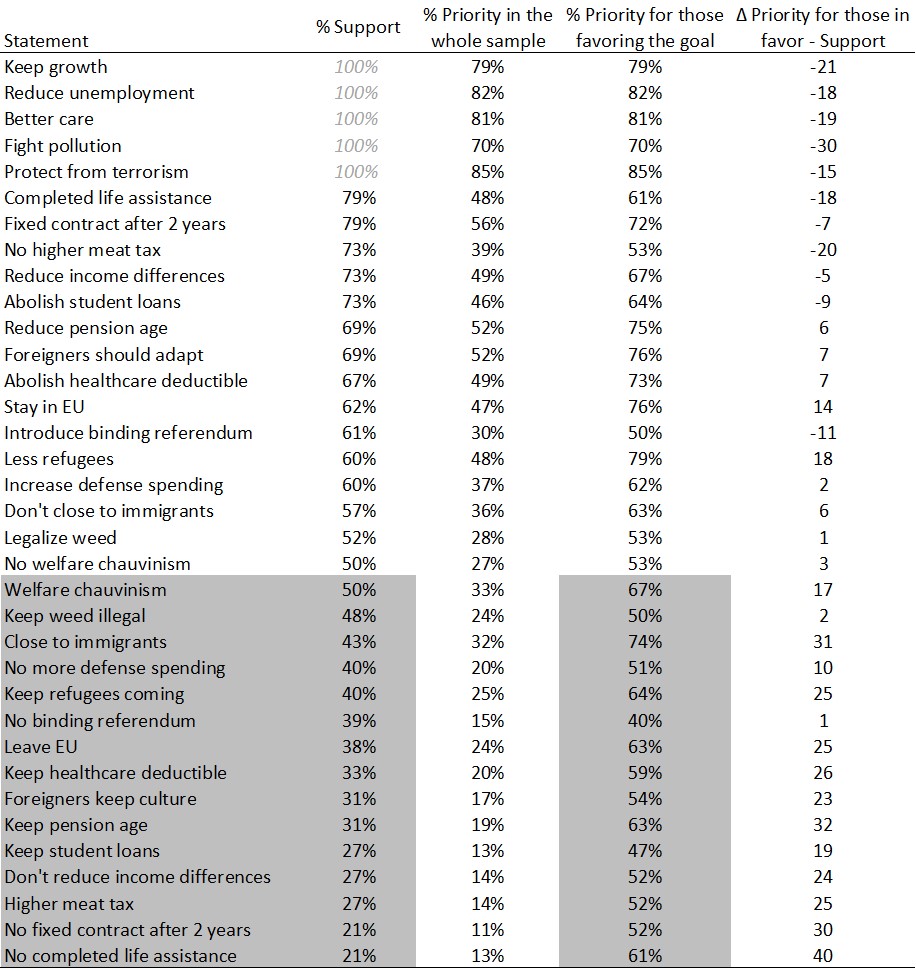

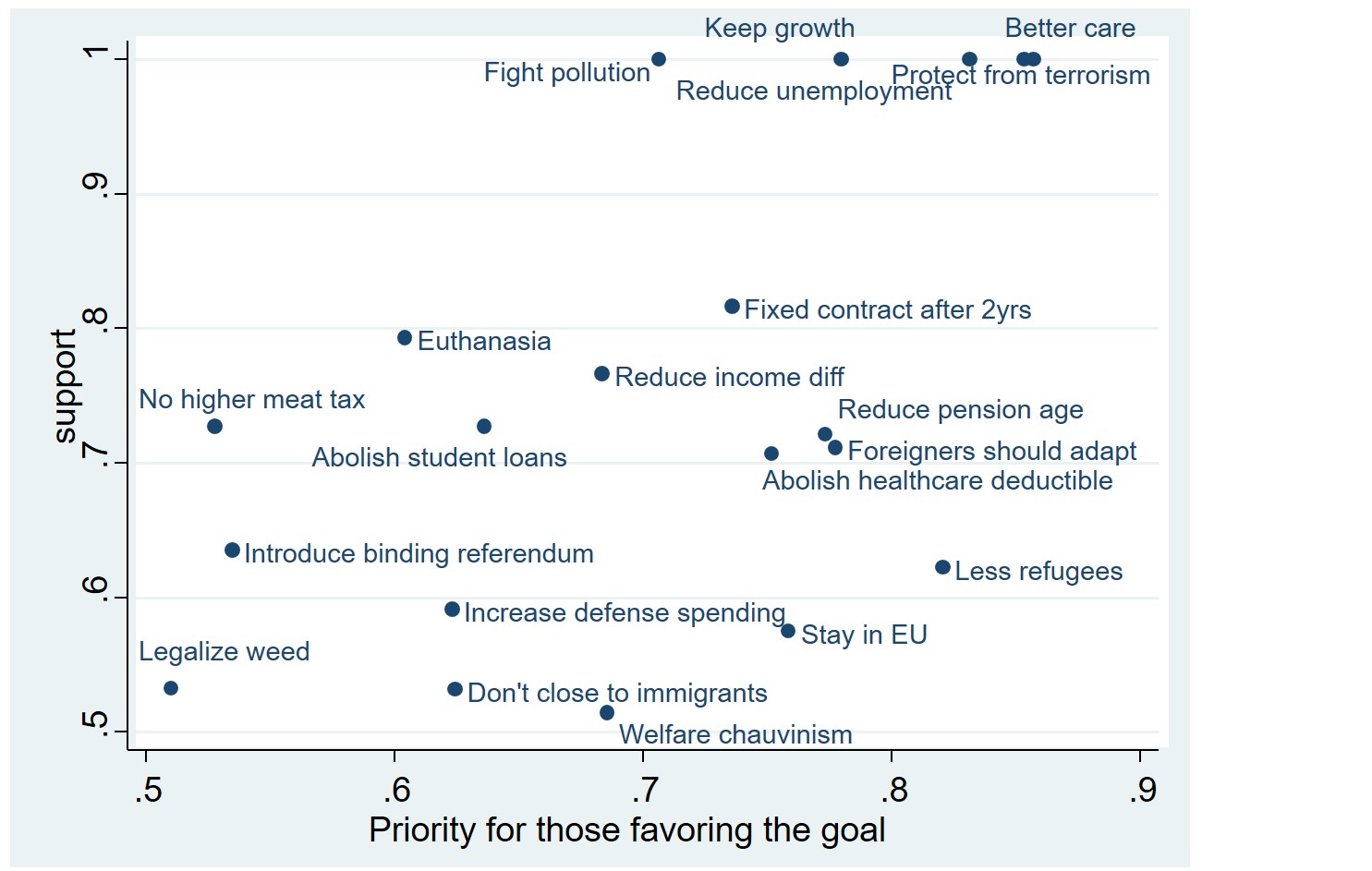

Table 1 presents the 36 rival goals (each of the 18 positional issues has two alternative sides) ranked by their level of support.

Table 1. Divisive goals by public opinion support, UK 2017

While in France there was a specific right-wing Zeitgeist, with four goals (negatively) related to immigrants supported by more than 70% of the electorate, in the United Kingdom an opposite left-wing orientation can be detected. With the only relevant exception of a largely supported welfare chauvinist goal (‘Restrict access to welfare benefits for immigrants’, supported by 76% of the respondents[2]), the other 7 out of the 8 most supported goals can be considered as belonging to a ‘leftist agenda’. Specifically, traditional economic leftist goals dominate the top positions of Table 1. Indeed, the 80% of British voters would like to increase the minimum wage and the 79% would like to ban the zero hours contracts for workers. Moreover, more than 70% of voters would like to use the tax leverage to spend more money on health and public services, to build affordable homes, reduce income differences and the cost of university tuition fees. What is more, about two thirds of the voters would like to nationalize Britain’s railways. Beyond the economic goals, another leftist, or liberal, goal (‘Keep the law that allows gay marriages’) is highly supported (73%), thus showing the fundamental secularism of the British society, consistently with the results previously shown in the Netherlands and France (see Emanuele, De Sio and Van Ditmars 2017; Emanuele, De Sio and Michel 2017). In other words, beyond the need to be protected from terrorist attacks and the other valence issues (not analyzed here), a traditional labourist agenda seems to be the favorite option for British voters in this electoral campaign. Nonetheless, we still need to see whether the Labour party will be able to exploit this favorable window of opportunity, or whether, instead, the Conservatives will be able to shift the public attention to other issues (i.e., the protection from terrorism or other shared goals on which they are considered as more credible).

The support accorded by voters to different goals tells only a part of the story. We also need to detect whether these goals are somewhat connected in a consistent way in voters’ mind. In other words, we want to understand if a traditional left-right dimension of competition still exists, and if this dimension is still the most important one. Or, instead, whether the mind of the voters is no longer ideologically consistent, at least according to a 20th-century fashion.

In order to do that, we performed an exploratory factor analysis based on the 18 positional issues presented above.

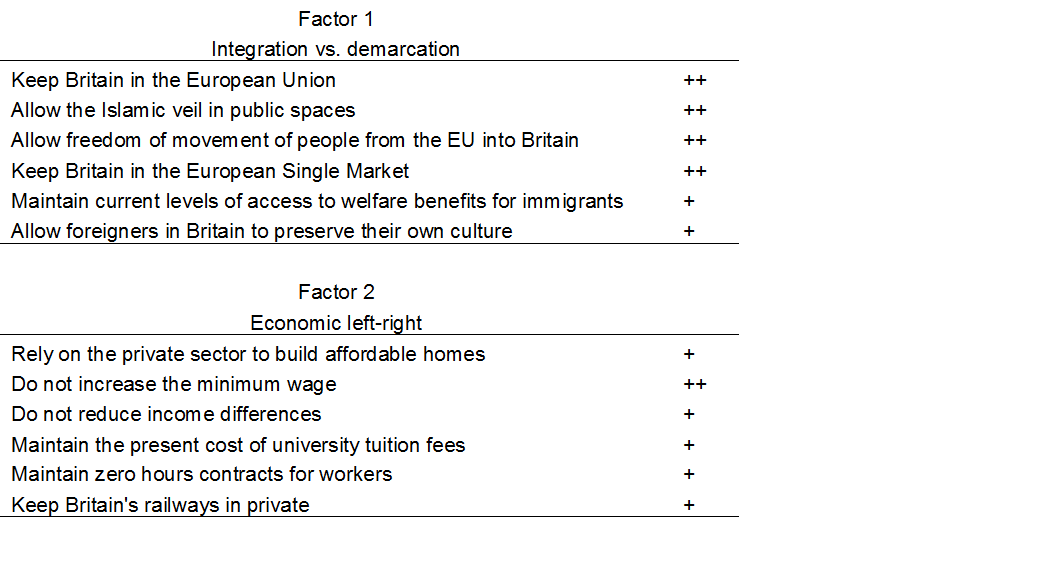

Table 2. The two main components and the most important rotated factor loadings (‘+’ = 0.4-0.7; ‘++’ = > 0.7)

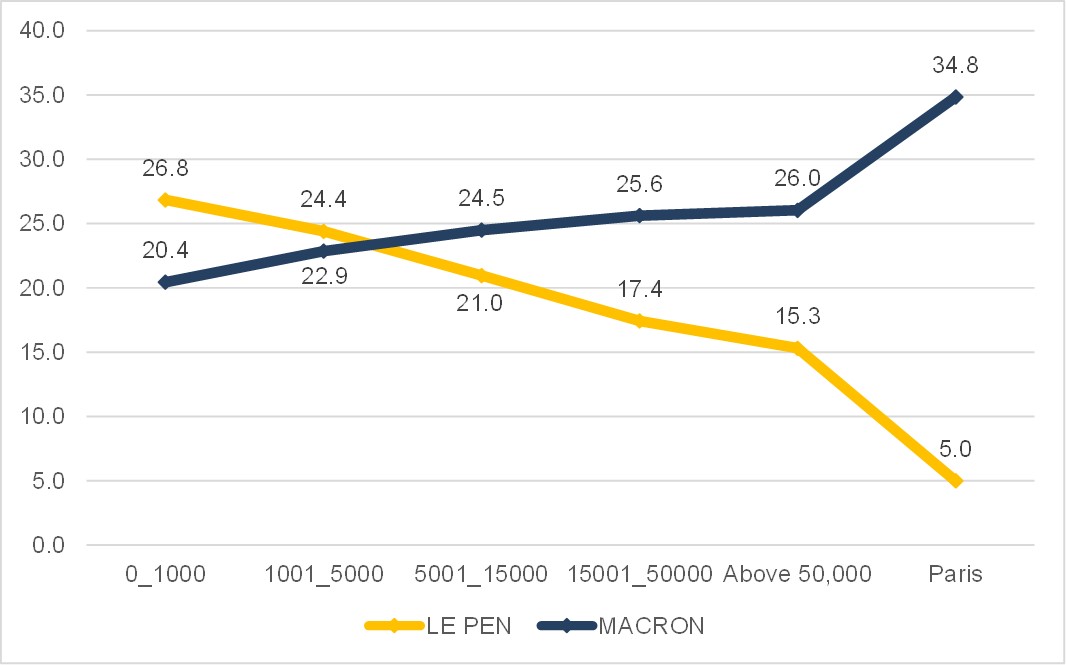

Table 2 reports the results of the exploratory factor analysis. The two most important components are reported. They account for the 36% of the variance[3]. Respectively, the first component explains a variance (e.g., Eigenvalue) of 3.5, while the second component has an Eigenvalue equals to 2.97. Quite surprisingly, the first and most important component (in terms of explained variance) is not the economic left-right dimension, which instead comes second, by adding a 16.5% of explained variance. Conversely, with a 19.5% of explained variance, the most important detected dimension of competition puts together the three issues related to the European Union (Brexit, the Single Market, and the freedom of movement of people) and the three cultural issues related to immigrants (Islamic veil, welfare chauvinism, and preservation of foreigners’ culture). This dimension can be clearly associated with the Kresi et al.’s integration/demarcation dimension (2006). This is a relatively new dimension that is gaining increasing momentum. It creates new alignments and is strategically exploited by the challengers of the status quo (such as Wilders in the Netherlands and Le Pen in France)[4] by pooling together issues related to the European Union, immigration, and (in France) globalization. This dimension blends together institutional, cultural, and economic goals, thus going beyond the traditional left-right axis, now consistently represented by the second component of the factor analysis reported in Table 2. This second component is now deprived by its cultural aspects and is only made by economic goals. A further evidence that the political space, in the United Kingdom as in many other countries, has become (at least) two-dimensional.

References

Emanuele, V., De Sio, L., and Van Ditmars, M. (2017), ‘Towards the next Dutch general election: issues at stake, support and priority’, /cise/2017/03/10/towards-the-next-dutch-general-election-issues-at-stake-support-and-priority/

Emanuele, V., De Sio, L., and Michel, E. (2017), ‘A shared agenda, with a right-wing slant: public opinion priorities towards the French Presidential election’, /cise/2017/04/18/a-shared-agenda-with-a-right-wing-slant-public-opinion-priorities-towards-the-french-presidential-election/

Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S., and Frey, T. (2006), ‘Globalization and the transformation of the national political space: Six European countries compared’, European Journal of Political Research, 45(6), 921-56.

Stokes, Donald E. (1963), ‘Spatial Models of Party Competition’, American Political Science Review 57 (2): 368–77.

[1] Additionally, the questionnaire also included ten valence issues (Stokes 1963), namely issues that refer to one shared goal, over which a general agreement is assumed (e.g., protection from terrorism). These issues have been excluded from this analysis, since a support of 100% was set by design.

[2] This results are consistent with what already seen in France, where the issue related to welfare chauvinism was supported by 70% of the respondents (while in the Netherlands only 50% of the voters supported this goal).

[3] The analysis performed reported also a third and a fourth factor, later excluded since they added a very small contribution to the explained variance (respectively, 9.8% and 5.7%).

[4] While usually silenced by mainstream, pro-global and pro-EU parties, in the French Presidential election of 2017, the other side of the conflict (the pro-European one) has been clearly politicized for the first time, thanks to the campaign led by Emmanuel Macron.