Dr. Alistair Clark

Newcastle University

The UK goes to the polls on the 7th May 2015 in what is widely expected to be the tightest and most uncertain general election contest since the 1970s. Like many other countries, the UK is facing a highly sceptical and volatile electorate, a populist right-wing insurgency, pressure from secessionists and the breakdown of what many comparative scholars have long held to be a defining characteristic of British politics, the two-party system. There are a number of things that are likely to be major issues in the election. Six of the most important are as follows.

No overall ‘winner’

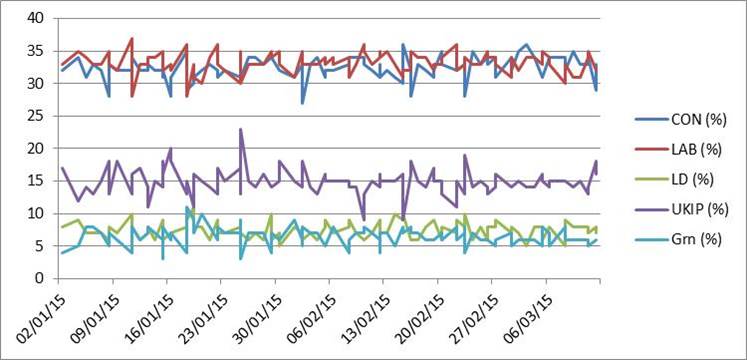

Although the two main parties, Conservatives and Labour, say that they are working for a majority, the main expectation for the 2015 general election among experts is that there will be no overall ‘winner’. As figure 1 shows, the polls are very tight, and they have narrowed considerably as the election gets closer. At one point in late 2012-early 2013, Labour was in the high 30%-low 40% range, with the Conservatives in the low 30% area. However, in the 103 Britain-wide polls conducted between the start of January 2015 and 17th March 2015 (the date of writing), the Conservative Party has averaged 32.3%, Labour 33.2%, the Liberal Democrats 7.5%, UKIP 14.8% and the Greens 6.5%. The gaps between the two main parties have mostly been well within the margin of error. One party is making large gains however. In the last four polls conducted in Scotland, the Scottish National Party (SNP) have averaged around 46% of the Scottish vote and a lead of 19-20 points over Labour.

Figure 1: Opinion Polls, Jan-Mar 2015

Source: UK Polling Report, http://ukpollingreport.co.uk/voting-intention-2 [17/3/15].

With 650 seats, a party needs 326 to form a majority. In reality they need a couple less because the Irish Republican party Sinn Fein does not take up its seats. Seat forecasting has become a minor industry in the UK. Recent predictions have both main parties on roughly the same number of seats. A recent UK Political Studies Association poll of psephologists and other experts (mainly political journalists) put the Conservatives on 278 seats, Labour on 282, Liberal Democrats on 25, UKIP on 7, the SNP on 29 with the rest taken up by various others including the Northern Irish parties. The academic ‘UK election forecast’ site currently puts the Conservatives on 286, Labour on 274, SNP on 42, Liberal Democrats 25, and UKIP only 1, with others filling the balance. In short, there is considerable uncertainty even amongst experts. The key themes are the main two parties on roughly the same number of seats, the Liberal Democrats losing more than half but still having a sizeable parliamentary group, the SNP winning the vast majority of Scottish seats and UKIP not doing as well as their media coverage would suggest.

Crisis of Major Parties and Leadership

Britain is no stranger to the anti-party mood circulating Europe. Party identification has been in steep decline for decades with strong identifiers at no more than 10%. Party membership levels are among the lowest in Europe assessed as a ratio of members to electors. Parties have been affected by a range of factors. These include their inability to resolve the economic crisis without causing damage to public services and household finances, a seeming powerlessness in the face of global economic and political events, and a history of over-promising and under-delivering in policy terms. Recent British election studies have emphasised the importance of valence and performance. Yet parties’ performance in office has often disappointed and all three main parties can now be held responsible for policies during the long economic crisis.

Table 1: Leadership and Party Ratings

|

Leader % |

Party % |

Difference +/- % |

|

| Cameron |

39 |

33 |

6 |

| Miliband |

30 |

52 |

-22 |

| Clegg |

31 |

40 |

-9 |

Source: IPSOS-MORI (Fieldwork 8-11 March 2015).

Recently, some highly unconvincing leadership has been evident for all the main parties. David Cameron has long been criticised by the right of the Conservative Party for being too centrist and failing to win a majority in 2010. Yet, he remains an asset for the Conservatives amongst voters. A recent IPSOS-MORI poll found 6% more of those polled liked Cameron as compared to those who liked the Conservative Party. Miliband remains a problematic leader for Labour and is 22% behind his party in popularity. Nick Clegg suffers a similar disadvantage for the Liberal Democrats, the result of unpopular decisions made in the early days of coalition. The days of popular leaders appear long over. Expect whichever of the two main party leaders loses the election to resign shortly afterwards.

Territorial Fragmentation

Forget what the old textbooks tell you about Britain being a two-party system. At the electoral level, it has not been that way for some time even if the first-past-the-post electoral system protected the two main parties in parliament (Clark, 2012: 12). What has become particularly acute in recent years is a territorialisation of the vote. Indeed, it is possible to talk of the UK’s party systems in the plural, not singular, each of which has different patterns of competition and opposition. The south of England is largely dominated by the Conservatives. The North of England has traditionally been Labour territory, with the Conservatives embedded in some wealthier areas. Both North and South have seen Liberal Democrat insurgencies in areas and in local government. The devolved assemblies all have higher scores on the effective number of parties (ENP) indicator, whether in parliament or the electorate (Clark, 2012: Ch. 7). Northern Ireland has long been a case apart, with five different party options there. In Wales and Scotland, the two nationalist parties are major actors and both have participated in devolved government. Plaid Cymru, the Welsh Nationalists, are currently the main opposition in the Welsh Assembly. The SNP are a majority government in Scotland and on the way to winning the majority of the 59 Scottish seats at Westminster for the first time. The inability of the two main parties to secure a majority means that this territorialisation has potentially severe constitutional consequences as potentially the SNP or Northern Irish Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) may be needed to support a minority government. If this happens, there is likely to be a backlash in England.

Rise in Small Parties

The decline in the two main parties’ popularity has given smaller party options the space to develop their support. The United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) has risen on the back of Euro-sceptic feeling, and done particularly well in European elections coming first in 2014 on 24 seats and 27.5%. It also won two by-elections towards the end of 2014. It has appealed to those feeling ‘left behind’ by modern society, often clustered in coastal areas of Southern England. Importantly, it has taken votes from both Conservative and Labour parties, and also in the North of England. Its main campaign themes have primarily been anti-EU and anti-immigration. Party leader, Nigel Farage, has cultivated an image of the straight-talking man who tells it like it is. However, UKIP suffers from regular indiscipline, and an over-reliance on Farage. Even if it does well in vote share, it is likely to win many fewer seats than its performance in the 2014 European elections might have suggested, not least since the Conservative Party is already offering an in-out referendum on the EU.

The other smaller party to have enjoyed some success recently is the Green Party. It succeeded in having an MP elected to parliament in Brighton in 2010, an area of local strength for the party. It has since experienced a rise in membership and in its polling numbers. It has also benefited in Scotland on the back of pro-Independence feeling after the referendum. However, a recent poor media performance by party leader Natalie Bennett has meant that the party made headlines for the wrong reasons. While it may hold on to its seat, the electoral system means that the Greens will find it difficult to make progress elsewhere. Their inclusion in a party leaders’ televised debate however is an important opportunity for them to gain further recognition.

Government Formation

Assuming that none of the two main parties makes a breakthrough and wins a majority, the UK will again experience an unfamiliar political process: the need to form either a coalition or minority government. Officially, both main parties are campaigning for a majority. As highlighted above, next to no-one thinks that will happen. In mid-March, what appears most likely is either a single-party minority government or potentially a coalition between either main party and the Liberal Democrats. Less likely is some form of right-wing coalition between the Conservatives, and the DUP from Northern Ireland, with or without UKIP. Labour, on the back of pressure from the Conservatives and English media, have recently been forced to rule out a formal coalition with the broadly centre-left SNP. Indeed, both the SNP and DUP had already actually ruled out formal coalition. However, that leaves open the possibility of issue-by-issue support and some form of broad understanding short of coalition, which remains very possible, if not likely, on both sides of the left-right spectrum.

The process of government formation will be much more complex than the previous experience of 2010. Then in reality there was only one feasible option – Conservative and Liberal Democrat. This time there are potentially many more actors involved, with interests which will have to be negotiated. In 2013, government formation in Italy took 61 days. In 2010 in the UK, it took a remarkably short 5 days. It is likely to take longer after 7th May if no majority emerges, although there will be considerable media pressure to do so sooner. The process is also not well understood in Britain, not least since British politicians have little experience of coalition and minority negotiations. Constitutionally, the incumbent government has the right to see if it can form an administration first. It stays in office as caretaker until a new government is formed. In practice, in 2010 the Liberal Democrats ignored this and publicly stated they would open negotiations with the largest party (the Conservatives) first. How the process of forming a government will run in 2015 is unclear, as with many things under Britain’s uncodified constitution.

Additional problems

Several other issues are likely to come to public attention after the elections. Firstly, the first-past-the-post electoral system famously delivers unrepresentative results. It is likely to do so again, with small parties and those with broad support disadvantaged. The chance to reform the electoral system was missed in 2011 when a referendum voted against a change to the alternative vote system. Currently the system benefits Labour, mainly because of a range of demographic and vote distribution reasons. Changes to constituency boundaries and to reduce the number of MPs to 600 (from 650), aimed at making the system more equitable, were dropped as a result of internal coalition disagreements during the 2010-15 parliament. If the Conservatives form the basis of a government, they may be revived. However, electoral reformers seeking a more proportional electoral system are likely to be disappointed; it is difficult to see what incentive either of the two largest parties would have in giving up their advantage under FPTP.

Secondly, the UK is in the process of changing its electoral registration system from one where the head of household ensured those living at an address were registered, to one of individual registration where voters are required to show some form of identification at the polls. The concern was that household registration was more open to fraud. However, the result has been large numbers of people dropping off the electoral register, with a particular problem evident in the registration of university students who have all but disappeared from electoral rolls. Various programmes are currently underway to try to encourage registration. We will know how successful this was closer to the election. Individual registration is also likely to cause problems on polling day. Unlike Italy, the UK does not have any form of personal identification card and the British are not required to carry such identification. There is potential here for people being denied the vote because they are not carrying their passport, driving licence or other approved identification. It would therefore be very surprising if there were not some registration controversies post-election.

Finally, the polling industry has come in for heavy criticism in recent months. Partly this was because the Scottish referendum ended up being so close, and pollsters did not pick this up until late in the day. Partly it is also because they have failed to identify one party or another establishing a clean lead in the run up to 2015. This is however hardly the pollsters’ fault. Reminiscent of Noelle-Neumann’s spiral of silence and the ‘shy Conservatives’ who delivered a Conservative government in 1992 against expectations of a Labour victory, many Scottish voters failed to identify their preferences in the 2014 referendum. It is entirely possible that the same dynamic is happening in the general election. Whatever the case, watch out for some calls to investigate the polling industry.

Biographical note

Dr Alistair Clark is currently Senior Lecturer in Politics at Newcastle University, a member of the UK Political Studies Association Executive Board and co-editor of British Journal of Politics and International Relations. His publications include Political Parties in the UK (Palgrave 2012) and recently in Public Administration an assessment of electoral integrity in Britain. This blog was written while he was a Visiting Professor in Political Science & School of Government at LUISS Guido Carli in Rome. E: alistair.clark@ncl.ac.uk. Twitter: @ClarkAlistairJ